Valentin Serov: The Master of the Psychological Portrait

by Cathy Locke

«Sunlit Girl. Portrait of M.Ya.Simonovich,» 1888, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

«Sunlit Girl. Portrait of M.Ya.Simonovich,» 1888, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The background and life of Valentin Serov (1865-1911) exemplified the transition of Russian culture and art from the age of realism to Russia’s Silver Age. His father, Alexander Serov (1820-1871), was an upper class lawyer who became recognized as a music critic and composer. Although he had good connections with the ruling elite, Alexander was well known for his volatile personality. Valentine’s mother, Valentina Bergman (1846–1924), was an accomplished pianist who composed operas and who had also helped her husband complete his last works. Her parents were Russified Jews. She had strong opinions on politics and was very involved in populist causes. Alexander and Valentina quickly drifted apart when Serov was four. In addition to an age difference of twenty-six years, Serov’s father liked luxury and his mother preferred a simple, spartan life. When they broke up, Serov’s father took a mistress and died two years later.

In 1874, Serov’s mother moved the family to Paris. This is where he first met Ilya Repin, who become his teacher at his mother’s insistence. Repin had Serov draw plaster casts and street scenes. In 1879 the Serovs moved back to Moscow where Valentin continued his studies with Repin at a famous artists’ colony, Abramtsevo, owned by the Mamontov family who were distant cousins of Serov’s father. Saava Mamontov had gained great wealth building railroads across Russia. Serov’s mother provided little care for him, so Elizaveto Mamontov took him in as her son. She introduced him to the cultural elite, which later provided him with the patronage he needed to become successful.

At the age of sixteen, Serov entered the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg, where he was not considered a brilliant student. He was friends with fellow students Mikhail Vrubel and Issac Levitan, who were also at the Academy. Along with his friends, Serov joined the artist group called the World of Art. Repin was teaching at the Academy while Serov was a student there. It was through Repin that Serov learned to take a psychological approach to his work. In all of his portraiture, Serov always made a statement about the person he painted. At the age of twenty-two, Serov received his first taste of fame with his Impressionist painting Girl with Peaches, which was immediately purchased by Pavel Tretyakov.

In 1897 Serov began teaching at the Moscow School of Painting and in 1898 he transferred to the Imperial Academy. In 1905 Serov witnessed the killing of peaceful protestors, which became known as Bloody Sunday, from his studio at the Academy. After this event, Serov refused to paint any of the members of the Imperial family and returned to the Moscow School of Painting. Many of Serov’s students in Moscow were involved in a number of different Avant-Garde groups including the Blue Rose and the Jack of Diamonds. These students had an influence on Serov’s style. In the last few years of his life he worked only in tempera paint and began flattening out his subject matter as his subjects shifted from portraiture to themes from classical mythology.

In 1889 Serov married Olga Trubnikova with whom he had two sons, Yura and Sasha. By this time, Serov was becoming Russia’s preeminent portraitist. Serov was always very business-like and even wore a suit when he painted. He had a serious personality and had inherited some of his father’s temper. Once, while painting a portrait, he stormed out of his client’s house because he was not asked to join them for lunch. As a family man, Serov spent money very freely, often beyond his means. He traveled and exhibited extensively throughout Europe most of his life. In 1908 he became a full member of the Vienna Session. He also exhibited at the Royal Academies of Venice, Berlin and London. In 1900 he was awarded the Grand Medaille d’Honneur at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. When he died of a stroke in 1911, he left no money for his family and, in fact, it was his friends who had to pay for his funeral.

Serov’s Technique:

- Serov’s style was very new; it was highly influenced by the Impressionist and what was coming out of France at the time.

- First he created the shape and then with one color he filled in the shape, creating color blocking. Very similar to what Gauguin was doing at the time.

- Serov always was searching for the right colors, composition and elements to use to show the true personality of the person.

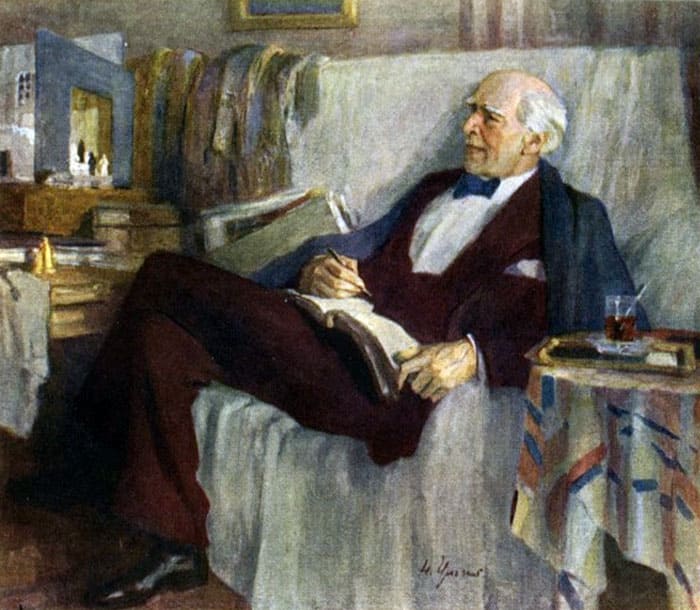

«К. С. Станиславский за работой», Ульянов

Год написания: 1947Размер: НеизвестенМестонахождение: Третьяковская галерея, Москва

Вариант 1 — Кратко

12 предложений/ 125 слов

Картина Николая Ульянова «К. С. Станиславский за работой» — это портрет знаменитого режиссёра и актёра Константина Станиславского, написанный художником уже после смерти последнего. На полотне герой изображён в интерьерах своего кабинета.

Пожилой седовласый мужчина сидит, закинув ногу на ногу, в широком белом кресле. Слева от Станиславского стоит небольшой круглый столик, где лежит поднос с чаем и выпечкой. Справа расположился стол побольше, заполненный самыми разными вещами. Тут же на кресле висит какая-то ткань.

Станиславский держит в руках тетрадь и ручку. Рядом с ним лежат картонные папки с эскизами. Режиссёр увлечённо обдумывает что-то, устремив взгляд перед собой и сдвинув густые белые брови.

Одет герой в элегантный тёмный костюм с галстуком-бабочкой. Кажется, будто режиссёр только что вернулся с представления и тут же стал размышлять над сюжетом новой пьесы.

Вариант 2 — Подробно

20 предложений/ 253 слова

Картина «К. С. Станиславский за работой» кисти художника Николая Ульянова — это во многих отношениях удивительное произведение. Прежде всего, интересно то, что портрет писался не с натуры, а был создан уже после смерти режиссёра, как дань уважения его таланту

Ульянов долгое время сотрудничал с МХАТом, где работал великий реформатор, поэтому художник просто не мог не почтить этого человека своим вниманием

На картине народный артист и режиссёр изображён в интерьерах своего кабинета. Мы видим широкое светлое кресло, в котором удобно расположился Константин Сергеевич, закинув ногу на ногу. Слева от героя стоит небольшой круглый столик, покрытый цветной скатертью. На скатерти лежит поднос с чаем и выпечкой, чтобы мужчина мог в нужный момент перекусить, не отрываясь от работы.

Справа от Станиславского расположился стол побольше, весь заставленный деревянными коробками и шкатулками. Здесь же лежат картонные папки и стоят белые фарфоровые статуэтки. На угол кресла накинута пёстрая ткань. Словом, в кабинете царит творческий беспорядок, но это ничуть не смущает героя.

Станиславский изображён уже пожилым человеком. Он одет в тёмный классический костюм, на шее героя повязан галстук-бабочка. Возможно, режиссёр только что вернулся со светского мероприятия и тут же принялся за работу.

В руках Константин Сергеевич держит тетрадь и ручку. Он сосредоточенно смотрит перед собой, нахмурив густые седые брови, словно обдумывая что-то значительное. Голова Станиславского повёрнута вправо, поэтому зритель может хорошо разглядеть гордый профиль режиссёра с орлиным носом и острым, выдвинутым вперёд подбородком.

Рядом с мужчиной на кресле лежат ещё несколько картонных папок, из которых выглядывают цветные листы. Должно быть, там хранятся эскизы костюмов и декораций, используемые режиссёром для работы.

см. также:Все сочинения-описания картин