Уильям Моррис

У. Моррис. автопортрет

Английский прозаик, художник, поэт и социалист. Считается крупнейшим представителем второго поколения прерафаэлитов, признанный неофициальный лидер Движения искусств и ремесел.

Обеспеченная семья смогла дать художнику хорошее образование. На почве увлечения средневековьем и движению трактарианцев подружился с Эдвардом Берн-Джонсом.

Основными сюжетными линиями в картинах У. Морриса была легенда о короле Артуре. Этой идее был посвящен вышедший в 1858 году сборник «Защита Гвиневеры и другие стихи».

С 1859 года жил официальным браком с Джейн Берден. Она стала его моделью для многих картин.

Черты стиля

Художественные произведения автора по стилистике близки к фрескам. Четкие цвета и мягкое использование полутонов создает ощущение размытости. Его работам присуща высокая степень детализации.

Основные картины

- «Королева Гвиневра»;

- гобелен «Woodpecker»;

- фронтипис «News from Nowhere».

У. Моррис. Королева Гвиневра

У. Моррис. Обои с лиственным орнаментом

У. Моррис. Стилизованные растительные узоры

‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1888)

This is perhaps one of Waterhouse’s most famous paintings. The Lady of Shalott is a popular topic to link folklore and art, even though artists draw from Tennyson’s poem rather than the Arthurian legends. In the poem from 1832, the Lady of Shalott lives in a tower on an island in a river. She’s cursed so she can’t look outside at the real world. Instead, she can only view the world through its reflection. She sits weaving all day, recreating the scenes she sees in her mirror.

‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1888) by John William Waterhouse

‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1888) by John William Waterhouse

One day, she spots Sir Lancelot in the mirror and looks out of the window to see him properly. The mirror breaks and she realises what she’s done. The curse comes over her at last. She heads down to the river and sets off towards Camelot in her boat, but dies before she gets there.

The painting captures the point where she sets off in the boat. Here, the three candles represent her flickering life, with only one remaining lit. The wintry reeds in the foreground also reflect the Lady’s waning life. This version of the Lady very much symbolises the Woman as Tragic Figure. We have no idea what the Lady did to end up cursed, but she’s essentially being punished for having desires.

Punishing Women

Note, it’s only when she sees Lancelot that she chooses reality over reflections. The act of looking here becomes a rebellion against what she’s ‘allowed’ to do. Notice the fact Waterhouse has given his Lady red hair. In art, this often represents a fallen woman or some sort of scandal (Gibson 2018). Remember too that Victorian women wore their hair up when in public. They only wore their hair loose in the bedroom (Gibson 2018). Here, the Lady of Shalott defies this convention to wear her hair loose and flowing.

It’s interesting that so many artists choose to represent the Lady of Shalott based on the poem. In Le Morte d’Arthur, she is Elaine of Astolat. She falls in love with Lancelot and asks him to wear her token in a jousting tournament. He does so, albeit attending the tournament in disguise since Guinevere is there. When Lancelot is injured, Elaine nurses him back to health. Once recovered, Lancelot insults Elaine by offering to pay her for her services. He leaves the castle and ten days later, Elaine dies of heartbreak. As in Tennyson’s poem, she’s placed in a boat and drifts down the river to Camelot. Lancelot ends up paying for her funeral.

‘The Magic Circle’ (1886)

I’d argue we could say the same of ‘The Magic Circle’. This painting depicts a sorceress, drawing a magic circle with her wand, while she brews a concoction in her cauldron. This painting feels like it should be mythological, due to its setting. Yet Waterhouse has gone for a ‘mix and match’ approach to his set dressing, making it hard to find a place or time for the scene. Frances Fowle does note Waterhouse’s fascination with “the exotic”, which we can see here (2000). Unfortunately, this has a tendency to reduce people and places to stereotypes, rather than acknowledging them as the full people or places that they are.

‘The Magic Circle’ (1886) by John William Waterhouse

The sorceress holds a golden sickle in her left hand. These tools are usually ascribed to druids, who allegedly used them to harvest mistletoe. (I say ‘allegedly’ because remember, the druids didn’t write things down). Frances Fowle links the sickle with both the moon and the goddess Hecate due to its crescent shape (2000).

Crows surround the circle, yet don’t cross its boundary. In folklore, crows often represent death through their role as carrion birds, making them a regular sight on battlefields. A toad or frog also sits outside the circle, referencing witch trial reports in which such animals were believed to be witch familiars. Notice that these animals are outside the protective circle. In some ways, it feels like a ‘witchcraft-by-numbers’ painting, with recognisable tropes added to the image.

This painting doesn’t depict a specific sorceress or myth. Instead, it captures a moment of magic. The female enchantress is common in Waterhouse’s work, yet here, she’s not exactly ‘dangerous’, nor is she a tragic figure. We don’t actually know what she’s doing. She could be casting a protective spell over the local area for all we know. She focuses on her work, without gazing out at the viewer or even inviting our gaze. I think my favourite part about the painting is that it also avoids the ‘witch = ugly woman’ trope. Nor is she portrayed in a sexualised fashion. She’s simply a woman getting on with the job at hand.

Folklore and Art: Natural Bedfellows

We can see from these works that folklore and mythology provide plenty of inspiration for artists. The painters overlook or emphasise different elements of the stories so they can comment on the society around them. In the case of John William Waterhouse, his female characters are by turns child-like damsels and dangerous temptresses. This almost turns the men into one-dimensional figures, easily manipulated by the women around them.

It is important to remember that artists did need to make a living. Reflecting the social mores of the time was one way to gain acceptance and thus commissions. But how much have these representations of various myths and legends impacted the way we now ‘remember’ the stories? Do let me know what you think in the comments!

Жизнь

Родился в Риме, в семье художников. Позднее они переехали в Лондон, где Уотерхаус прожил всю оставшуюся жизнь. Поначалу живописному мастерству его обучал отец, в 1870 году юноша поступил в Королевскую Академию художеств .

В ранних работах художника чувствуется влияние Альма-Тадема и Фредерика Лейтона . В 1874 году, в возрасте двадцати пяти лет, представил на выставке картину «Сон и его сводный брат Смерть

», которая была хорошо встречена критикой и впоследствии выставлялась практически каждый год, вплоть до смерти художника.

В 1883 году Уотерхаус женился на художнице Эстер Кенуорти , чьи картины также появлялись на выставках Королевской Академии художеств. У них было двое детей, которые рано умерли, но, несмотря на это, брак был счастливым .

Изображен на британской почтовой марке 1992 года.

Модели для произведений искусства

Однако своей непреходящей популярностью художник обязан более всего очарованию его задумчивых моделей считается, что при написании полотна «Леди из Шалот» моделью была жена художника.

В 1908-1914 годах Уотерхаус создает ряд картин, основанных на литературных и мифологических сюжетах («Миранда», «Тристан и Изольда», «Психея», «Персефона» и другие). В этих картинах художник пишет свою любимую модель, недавно идентифицированную исследователями творчества Уотерхауса, Кеном и Кэти Бейкр, как мисс Мюриэл Фостер. Очень немного известно о частной жизни Уотерхауса — только несколько писем сохранилось до нашего времени и, собственно, много лет персоналии его моделей оставались тайной. Из воспоминаний современников также известно, что Мэри Ллойд, модель шедевра лорда Лейтона «Пылающий июнь», позировала и для Уотерхауса.

Любитель мифов

Джон Уильям Уотерхаус появился на свет в Риме, однако спустя некоторое время семья переехала в Лондон, где живописец прожил все последующие годы. Ещё в юности он интересовался старинными преданиями, античными мифами и английским фольклором. Несомненно, именно тогда в его воображении начали появляться образы, которые в дальнейшем художник перенесёт на свои полотна. Среди них были и русалки.

Как считают искусствоведы, популярность Джона Уильяма была обусловлена не столько особенной манерой письма или злободневностью сюжетов картин, сколько выразительной красотой моделей, изображённых им.

Девушки на картинах Уортерхауса часто пребывают в лирической задумчивости, что подкупало публику. Это придавало образу загадочности, а может ли быть сочетание более выигрышное, нежели красота и таинственность? В работах Уотерхауса часто можно заметить мечтательных или задумчивых героинь, но особенно хорошо это видно в его «Русалках».

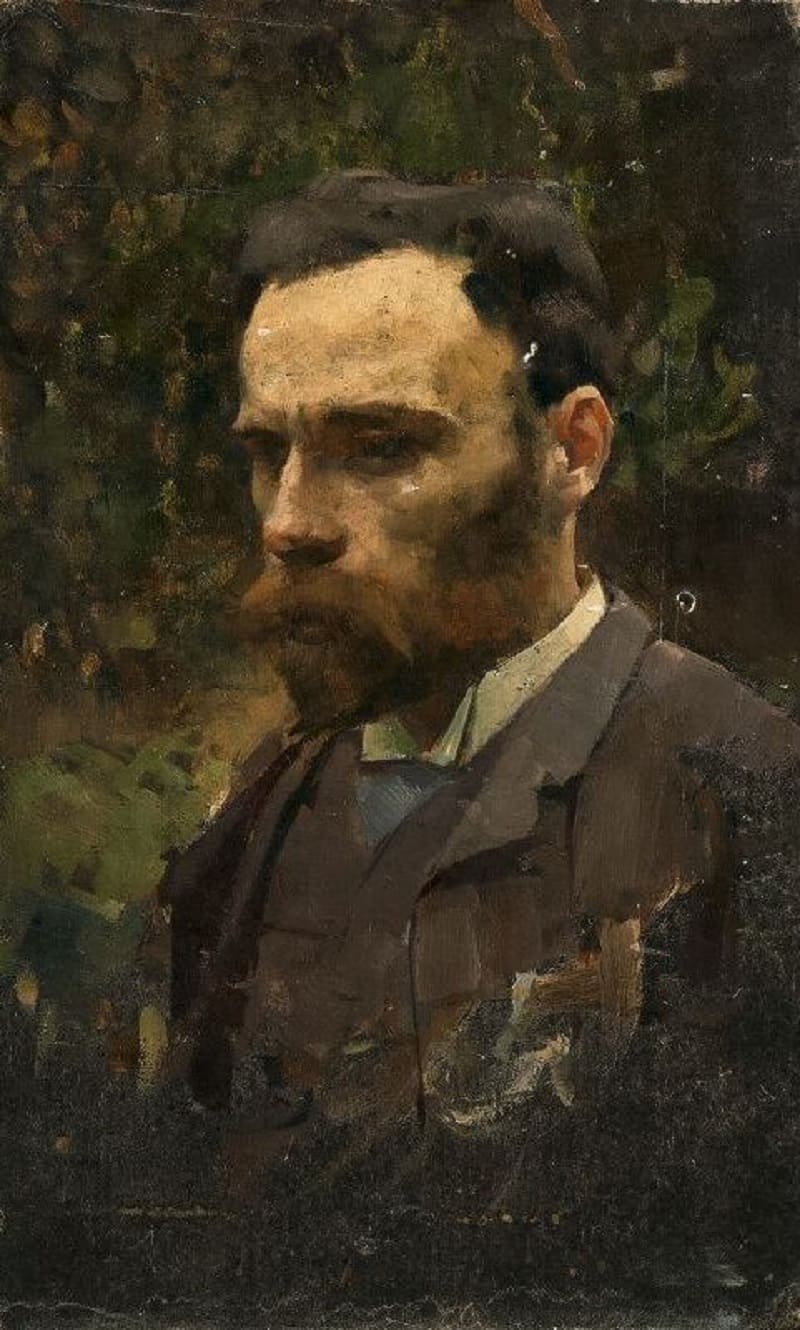

Уильям Логсдэйл «Портрет Джона Уильяма Уотерхауса», около 1887 годаМестонахождение: Национальная портретная галерея, Лондон Великобритания

Уильям Логсдэйл «Портрет Джона Уильяма Уотерхауса», около 1887 годаМестонахождение: Национальная портретная галерея, Лондон Великобритания

‘Pandora’ (1896)

Pandora is perhaps the ultimate woman to depict in art. She’s made both dangerous and tragic through her curiosity. Like the Lady of Shalott, her desire to look proves to be her undoing. Yet unlike the Lady, it proves the undoing for all humanity.

‘Pandora’ (1896) by John William Waterhouse

‘Pandora’ (1896) by John William Waterhouse

The most famous version of the Pandora myth comes from a poem by Hesiod. Zeus is furious after Prometheus gives fire to humans. He decides to give humanity a punishment in the form of a beautiful woman. At this point, the myths agree that the humans in the Golden Age were all men. The arrival of a woman becomes their punishment, so clearly, misogyny ran deep even then.

Hephaestus, the blacksmith god, creates Pandora, and the other gods give her skills and abilities. Hermes names her Pandora, which means ‘All-Gift’ to reflect the gifts she received from the gods.

Prometheus has warned his brother Epimetheus to reject any gifts from Zeus. He’s already figured that there will be reprisals. Yet Pandora is so alluring that Epimetheus accepts her, and the jar she brings with her. A mistranslation sees the jar turned into a box in the 16th century, which explains Waterhouse’s depiction of the box. Pandora unleashes the contents of the jar, except Hope, which remains inside.

Mythology or Misogyny?

There is some disagreement as to the ‘veracity’ of the myth due to the existence of a pre-Hesiodic goddess named Pandora. In this case, her name actually means ‘all-giving’. As William E. Phipps notes, “Classics scholars suggest that Hesiod reversed the meaning of the name of an earth goddess called Pandora (all-giving) or Anesidora (one-who-sends-up-gifts)” (1988: 37). Here, this earth goddess who brings life is recast as a woman who brings only death. Phipps also notes Hesiod’s general hatred of women, which clearly colours his myth of Pandora.

I think the Waterhouse version is interesting in that this Pandora doesn’t appear to know what is in the box. This version jettisons the ‘walking booby trap from the gods’ of Hesiod and favours the ‘curious woman’ interpretation. While this still places the responsibility for the world’s evils on Pandora, it also removes any malice on her part. In this painting, she seems naive and almost guileless. Still, like the Lady of Shalott, she’s punished for the desire to see.

Описание картины

Поэзия Теннисона была очень популярна среди прерафаэлитов, к которым примыкал Уотерхаус. Хотя в данном случае Теннисон пишет о трагической любви, художники (Холман Хант, Россетти, Артур Хьюз, Уотерхаус) всегда наполняли картины по «Волшебнице Шалот» своим смыслом и отражали мировоззрение людей Викторианской эпохи, избирая для иллюстрации разные сюжетные отрывки и по-разному интерпретируя статус женщины. Возрастала роль женщины как хранительницы домашнего очага, а прерафаэлиты, в то же время, показывали внутренний конфликт между частными, личными надеждами и общественными обязанностями женщин.

Уотерхаус изображает Леди из Шалот в тот момент, когда она уже сидит в лодке и держит в руках цепь, которая крепит лодку к берегу. Рядом лежит гобелен, когда-то являвшийся средоточием её жизни, а теперь забытый и частично погружённый в воду. Свечи и распятие делают лодку похожей на погребальную ладью, Элейн смотрит на них с грустным, одиноким и одновременно отчаявшимся выражением лица. В то время свечи символизировали жизнь, на картине две из них задуты. Автор намекает, что Элейн осталось жить совсем недолго. Рот девушки открыт: она поёт прощальную песню.

Пейзаж нарисован небрежно — Уотерхаус отступил от прерафаэлитских традиций, когда природа изображалась максимально достоверно и подробно.

What do you think of the work of John William Waterhouse?

References

Fowle, Frances (2000), ‘The Magic Circle: Summary’, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/waterhouse-the-magic-circle-n01572.

Gibson, Rachael (2018), ‘Why are artists infatuated with red hair?’, Art UK, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/why-are-artists-infatuated-with-red-hair.

Kestner, Joseph A. (1991), ‘Before “Ulysses”: Victorian Iconography of the Odysseus Myth’, James Joyce Quarterly, 28:3, pp. 565-594.

Phipps, William E. (1988), ‘Eve and Pandora Contrasted’, Theology Today, 45:1, pp. 34-48.

Silver, Carole G. (2011), ‘Waterhouse Revisited’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 39:1, pp. 263-269.