Later Work and Death

Joan Miró in his studio.

Alain Dejean / Sygma / Getty Images

In 1974, in his late 70s, Joan Miró created a vast tapestry for the World Trade Center in New York City working with Catalan artist Josep Royo. He initially refused to create a tapestry, but he learned the craft from Royo, and they began producing multiple works together. Unfortunately, their 35-foot-wide tapestry for the World Trade Center was lost during the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001.

Among Miró’s last works were monumental sculptures executed for the city of Chicago unveiled in 1981 and Houston in 1982. The Chicago piece was titled The Sun, the Moon, and One Star. It is a 39-foot-tall sculpture that stands in downtown Chicago near a monumental sculpture by Pablo Picasso. The brightly-colored Houston sculpture is titled Personage and Birds. It is the largest of Miró’s public commissions and stands over 55 feet high.

The Influence of Paris

Following graduation, Miro struggled to find recognition for his art in Barcelona. Instead, in 1920, he headed to Paris, meeting various Surrealist artists including Pablo Picasso, Andre Masson and Tristan Tzara, who had a profound impact on his practice.

Following his return to Montroig, Miro described how he “immediately burst into painting, the way children burst into tears.” In the years that followed Miro moved between Paris and Catalonia, spending Summers in Spain and winters in Paris. But he was desperately poor and described how he sometimes “saw shapes on the ceiling” following bouts of extreme hunger, which would make their way into his paintings.

Legacy

Joan Miró Mural in Madrid, Spain.

Bettmann / Getty Images

Joan Miró earned recognition as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. He was a leading light of the Surrealist movement, and his work had a significant impact on a wide range of Abstract Expressionist artists. His monumental murals and sculptures were part of a wave of important public art produced in the last half of the century.

Miró believed in a concept that he referred to as the «assassination of painting.» He disapproved of bourgeois art and considered it to be a form of propaganda designed to unite the wealthy and powerful. When he first spoke of this destruction of bourgeois painting styles, it was in response to the dominance of Cubism in art. Miró famously disliked art critics as well. He believed they were more interested in philosophy than the art itself.

Did you Know?

Miro’s first solo exhibition at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona was ridiculed by critics and the public, while some visitors even vandalised his artworks, prompting Miro to leave Spain for Paris.

Given this early bad reception, Miro developed a dislike for art critics, describing them as “more concerned with being philosophers than anything else. They form a preconceived opinion, then look at the work of art. Painting merely serves as a cloak for their emaciated philosophical systems.”

Writer Ernest Hemingway was a huge fan of Miro’s paintings and bought one of Miro’s artworks, La Masia, 1921-22, as a gift for his wife. Both Hemingway and his friend were keen on the same painting, depicting a farm in Catalonia, so they rolled a dice to see who would get it.

methods for making art, including finger painting, rubbing with his fists, and even stamping on the canvas with his bare feet – footprints are just visible in his painting Toile Brulee, 1973.

Miro and his Surrealist contemporaries were greatly influenced by the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud and attempted to induce altered states of mind to find subject matter for their paintings, including experimenting with “hallucinations of hunger.”

Miro only just escaped German forces in France during the outbreak of World War II. Living in Varengeville, he and his family caught the last train to Paris, and found space on the final train out of Paris into Spain.

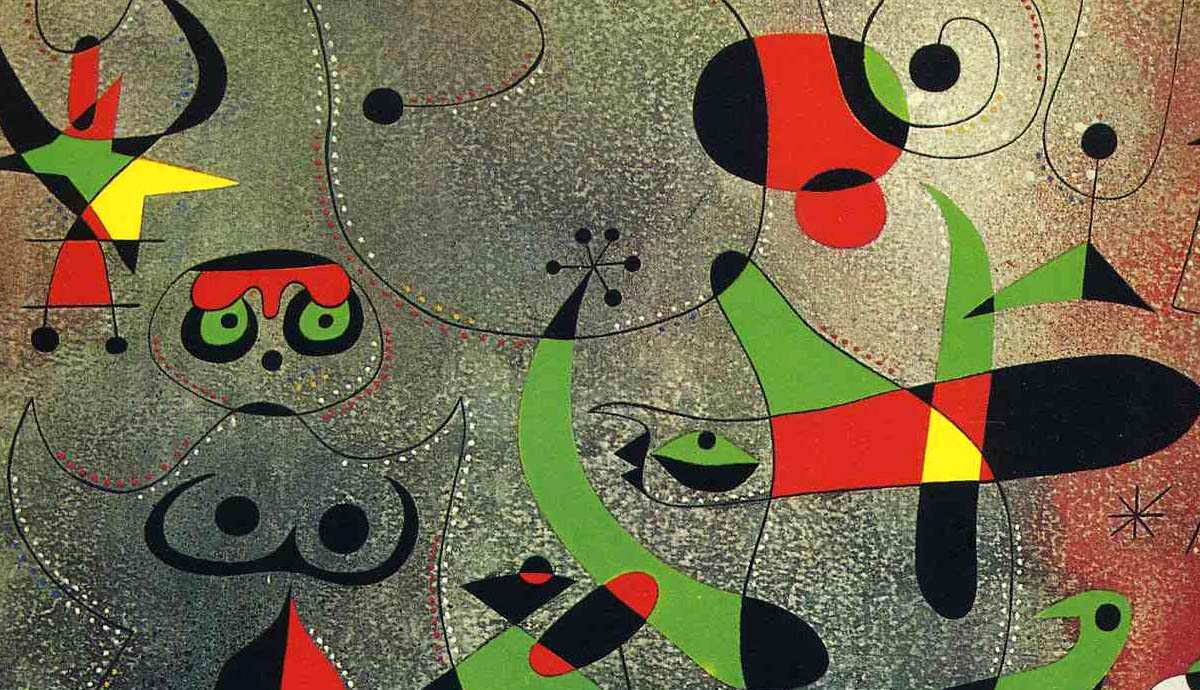

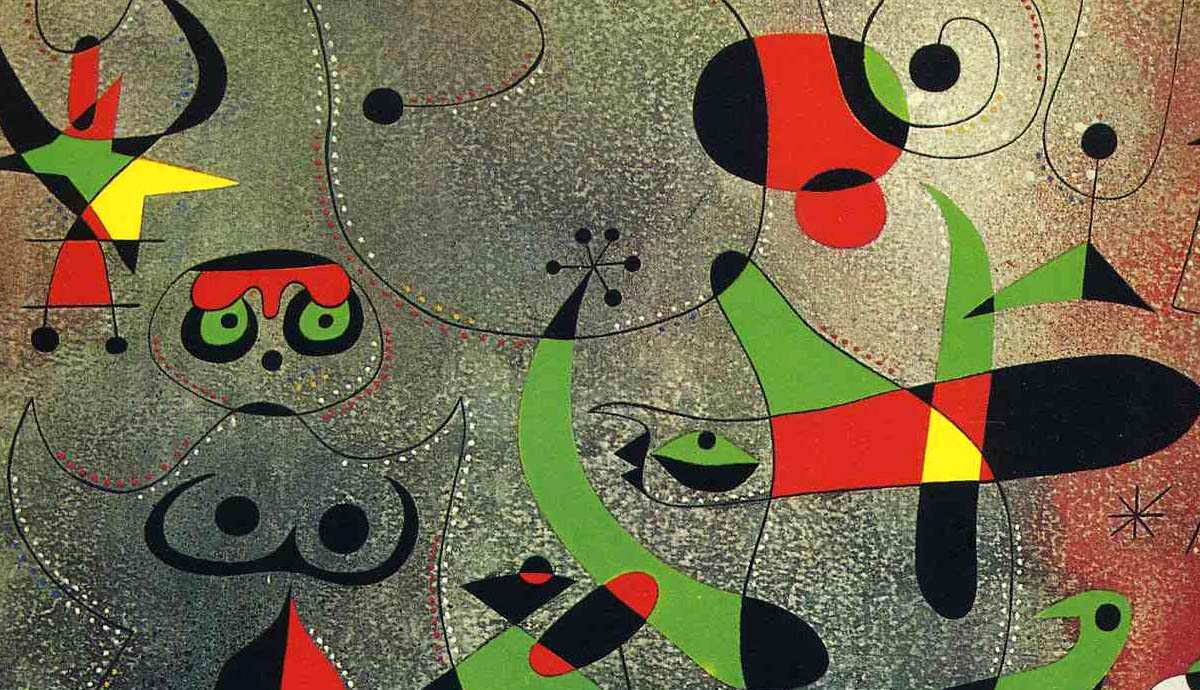

In relation to his fantastically Surreal later paintings, which feature biomorphic, ambiguous forms, art historians defined the term “miromorphosis.”

Miro designed a tapestry for the World Trade Centre in New York in collaboration with Josep Royo, titled the World Trade Centre Tapestry. Sadly, the tapestry was one of many artworks to be destroyed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The Fundacio Joan Miro, in the Parc de Montjuic in Barcelona, was founded in 1975 and houses a vast array of Miro’s artworks, including 217 paintings, 178 sculptures, 9 textiles and over 8,000 drawings.

Miro was astonishingly prolific and left behind a staggering body of work, including around 2,000 paintings, 500 sculptures, 400 ceramics, 5,000 drawings and over 1,000 prints, which exist in public and private art collections all around the world. He also made ceramics, murals and tapestries, and even designed costumes and props for the ballet, working well into his later years.

Joan Miro is one of the representatives of surrealism. Fundamentally avant-garde and modern, he demonstrates a very great creativity, in both his paintings and his sculptures.

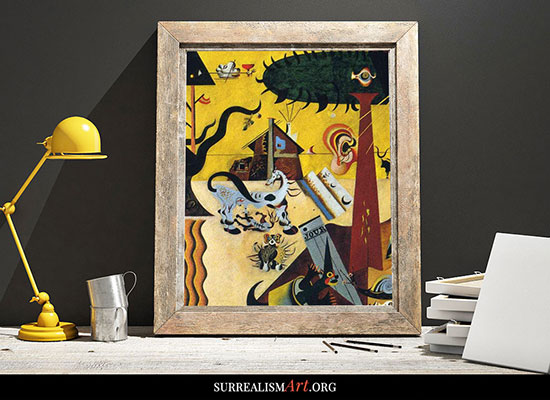

The Tilled Field artwork by artist Joan Miro

The Tilled Field artwork by artist Joan Miro

The origins, the journey of Joan Miro

Joan Miro was born in Barcelona in 1893. His father is a jeweler and his mother the daughter of a cabinetmaker. Joan began to paint very young, at the age of eight. He first began studying business in 1907 but that turns out to be a failure. So he abandoned his studies to join the School of Fine Arts of La Llotja.

At seventeen, Joan Miro becomes a clerk in a store until 1911 when he contracted typhus. For his health, he was forced to move to a family farm. It was at that moment he realized his attachment to the Catalan land where he regularly returns throughout his life. When he recovered, he joined the Barcelona School of Art in order to perfect his talent and become a painter. He then attended The Académie du Cercle Saint-Luc until 1918. He discovers modern art during a visit to the Dalmau gallery in Barcelona.

Joan Miro and surrealism

In 1919, he goes to Paris for the first time and joins, after experiencing Cubism and Fauvism, Surrealism. He feels comfortable with quirky humor and taste of the imagination of this current. Meanwhile, Miro lives an identity crisis. The exterior doesn’t inspire him anymore and he must question his art. He manages to solve his problems through artistic surrealism and relying on spontaneity in his painting and sculpture. The unconscious and the world of dreams are now the fertile soil in which Miro draws his paintings.

In 1925, he presented at an exhibition Carnival of Harlequin, purely surrealist work, and will now be known worldwide. When the surrealist movement takes too many political positions, Miro gets out of the group and dedicates to collage, lithography and sculpture.

Time of maturity

During the Spanish Civil War, Miró moves to Paris where he returns to a more realistic painting. When German troops arrive in France, Joan returns to Spain and finds his definitive style. He is henceforth recognized as a great Catalan artist.

At the end of his life, he devotes himself to monumental sculptures covered with ceramic. Joan Miro dies on Christmas Day in 1983.

Author

Arts3 Network

Websites Edition

Other articles

Max Ernst

René Magritte

Salvador Dali

“The more ignoble I find life. On n’est pas réceptif aux mêmes choses , on n’éprouve pas les mêmes émotions.”

See more quote by Joan Miro

Travel Info

- Joan-Miró Foundation

- Address: Parc de Montjuïc, s/n, 08038 Barcelona, Spain View map

- Phone: +34 934 43 94 70

- Website: fundaciomiro-bcn.org

Notes

- Miró’s art biography at guggenheimcollection.org.

- Janis Mink, Miró, (Los Angeles: Taschen, 2003 ISBN 9783822896099), 43.

- Maeght Foundation, Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- Jemma Montagu, The Surrealists: Revolutionaries in Art & Writing 1919-1935, (London: Tate Pub., 2002. ISBN 9781854373670), 15

- M. Rowell, Joan Mirό: Selected Writings and Interviews (London: Thames & Hudson, 1987), 114-116.

- Peter Schjeldahl, Angry Young Man — Joan Miro, Museum of Modern Art, The New Yorker, November 10, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Art Works Lost in WTC Attacks Valued at, Insurance Journal, October 8, 2001. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Personnage Oiseaux (Bird Characters), 1972-1978 Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Ulrich Museum of Art Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Martin H. Bush, The Edwin A Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University. Wichita, KS: The Edwin A Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, 1980.

- Miró’s mural as it appears installed on the façade of the Ulrich Museum, Wichita State University, Kansas. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Ateliers Loire, Chartres, France Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Joan Miró (Spanish), 1893-1983: Featured artist works, exhibitions and biography from Walton Fine Arts Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Joan Miró dies in Spain at 90 The New York Times, December 26, 1983. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Joan Miro (1893-1983) | Painting-Poem («le corps de ma brune puisque je l’aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c’est pareil») Christies.com, February 7, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2015

- BBC News — Joan Miro painting smashes auction record Bbc.co.uk, June 20, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Biography from the Guggenheim Museum lists some of his awards Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Biography from ArtNet lists Miro’s Gold Medal award from King Juan Carlos Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- The Pilar and Joan Miró Foundation in Mallorca, Spain Retrieved September 23, 2015.

Early Life and Career

Portrait of Vincent Nubiola (1917).

Courtesy Folkwang Museum

Growing up in Barcelona, Spain, Joan Miró was the son of a goldsmith and watchmaker. Miró’s parents insisted that he attend a commercial college. After working for two years as a clerk, he had a mental and physical breakdown. His parents took him to an estate at Montroig, Spain for recovery. The Catalonia landscape around Montroig became very influential in Miró’s art.

Joan Miró’s parents allowed him to attend a Barcelona art school after he recovered. There, he studied with Francisco Gali, who encouraged him to touch the objects he would draw and paint. The experience gave him a more powerful feeling for the spatial nature of his subjects.

Everything is Lost

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

The success of Miro’s career was brought to an abrupt end by the global depression and in 1932 he moved with his family back to Barcelona. A period of dramatic political instability followed – the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, followed by the outbreak of the Second World War. Miro and his family eventually made their way to Mallorca, although he was deeply unhappy, commenting, “I was very pessimistic. I felt that everything was lost.” In response, he made small, dark works on paper, titled Constellations, 1939-41, capturing the star filled night sky as a symbol of his desire for open space and freedom from war.

Did you Know?

Miro’s first solo exhibition at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona was ridiculed by critics and the public, while some visitors even vandalised his artworks, prompting Miro to leave Spain for Paris.

Given this early bad reception, Miro developed a dislike for art critics, describing them as “more concerned with being philosophers than anything else. They form a preconceived opinion, then look at the work of art. Painting merely serves as a cloak for their emaciated philosophical systems.”

Writer Ernest Hemingway was a huge fan of Miro’s paintings and bought one of Miro’s artworks, La Masia, 1921-22, as a gift for his wife. Both Hemingway and his friend were keen on the same painting, depicting a farm in Catalonia, so they rolled a dice to see who would get it.

methods for making art, including finger painting, rubbing with his fists, and even stamping on the canvas with his bare feet – footprints are just visible in his painting Toile Brulee, 1973.

Miro and his Surrealist contemporaries were greatly influenced by the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud and attempted to induce altered states of mind to find subject matter for their paintings, including experimenting with “hallucinations of hunger.”

Miro only just escaped German forces in France during the outbreak of World War II. Living in Varengeville, he and his family caught the last train to Paris, and found space on the final train out of Paris into Spain.

In relation to his fantastically Surreal later paintings, which feature biomorphic, ambiguous forms, art historians defined the term “miromorphosis.”

Miro designed a tapestry for the World Trade Centre in New York in collaboration with Josep Royo, titled the World Trade Centre Tapestry. Sadly, the tapestry was one of many artworks to be destroyed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The Fundacio Joan Miro, in the Parc de Montjuic in Barcelona, was founded in 1975 and houses a vast array of Miro’s artworks, including 217 paintings, 178 sculptures, 9 textiles and over 8,000 drawings.

Miro was astonishingly prolific and left behind a staggering body of work, including around 2,000 paintings, 500 sculptures, 400 ceramics, 5,000 drawings and over 1,000 prints, which exist in public and private art collections all around the world. He also made ceramics, murals and tapestries, and even designed costumes and props for the ballet, working well into his later years.

Legacy

Today, Miró’s paintings sell for between US$250,000 and US$26 million. In 2012, Painting-Poem («le corps de ma brune puisque je l’aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c’est pareil») (1925) was sold at Christie’s London for $26.6 million. Later that year at Sotheby’s in London, Peinture (Etoile Bleue) (1927) brought nearly 23.6 million pounds with fees, more than twice what it had sold for at a Paris auction in 2007 and a record price for the artist at auction.

Many of his pieces are exhibited today in the National Gallery of Art in Washington and Fundació Joan Miró in Montjuïc, Barcelona; his body is buried nearby, at the Montjuïc cemetery.

Sculpture, Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid

Sculpture, Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid

The Fundació Joan Miró Museum in Montjuïc, Barcelona

Awards

Joan Miró i Ferrà won several awards in his lifetime. In 1954 he was given the Venice Biennale print making prize, in 1958 the Guggenheim International Award, and in 1980 he received the Gold Medal of Fine Arts from King Juan Carlos of Spain. Miró received a doctorate honoris causa in 1979 from the University of Barcelona.

In 1981, the Palma de Mallorca City Council established the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca, housed in the four studios that Miró had donated for the purpose.

Joan Miro Foundation

The Fundació Joan Miró, Centre d’Estudis d’Art Contemporani (Joan Miró Foundation) is a museum of modern art honoring Joan Miró and located on Montjuïc in Barcelona, Catalonia.

The building housing the museum is itself a notable example of modern design drawing from regional traditions. It was completed in 1975 by architect Josep Lluís Sert, who conceived it like an open space, with big terraces and interior courtyards that allowed a correct circulation of the visitors. The building was broadened in 1986 to add the library and the auditorium.

The Foundation has also a space named «Espai 13,» dedicated especially to promote the work of young artists who experiment with the art. Also temporary exhibitions of works of other painters are carried out. Moreover, the foundation carries out itinerant exhibitions to introduce the work of the Spanish artist.

Painting and Poetry

Miro began studying art in Barcelona in 1912, where he discovered the work of various avant-garde artists and Catalan poets, writing, “I make no distinction between painting and poetry.” As a student he experimented with various techniques, including drawing “by touch” rather than sight.

His early paintings spanned various subjects including still-life, portraiture and landscape, characterised by vivid colours and expressive mark-making, which revealed the influences of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cezanne and the French Fauvist painters, combined with a love of the naïve, vibrant language of Catalan folk art.

Surrealism

Landscape (The Hare) (1927).

Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

In 1924, Joan Miró joined the Surrealist group in France and began creating what were later called his «dream» paintings. Miró encouraged the use of «automatic drawing,» letting the sub-conscious mind take over when drawing, as a way to free art from conventional methods. The famed French poet Andre Breton referred to Miró as «the most Surrealist of us all.» He worked with the German painter Max Ernst, one of his best friends, to design sets for a Russian production of the ballet Romeo and Juliet.

Shortly after the dream paintings, Miró executed Landscape (The Hare). It features the Catalonia landscape that Miró loved from his childhood. He said that he was inspired to create the canvas when he saw a hare dart across a field in the evening. In addition to the representation of the animal, a comet appears in the sky.

For a period in the late 1920s and the 1930s, Miró returned to representational painting. Influenced by the Spanish Civil War, his work sometimes took on a political tone. His most explicitly political piece was the 18-foot-high mural commissioned for the Spanish Republic’s pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition of 1937. At the end of the exhibition in 1938, the mural was dismantled and ultimately lost or destroyed.

Following this shift in his work, Joan Miró ultimately returned to a mature, idiosyncratic style of Surrealism that would mark his work for the rest of his life. He used naturalistic objects such as birds, stars, and women rendered in a surreal fashion. His work also became notable for obvious erotic and fetishistic references.

Everything is Lost

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

The success of Miro’s career was brought to an abrupt end by the global depression and in 1932 he moved with his family back to Barcelona. A period of dramatic political instability followed – the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, followed by the outbreak of the Second World War. Miro and his family eventually made their way to Mallorca, although he was deeply unhappy, commenting, “I was very pessimistic. I felt that everything was lost.” In response, he made small, dark works on paper, titled Constellations, 1939-41, capturing the star filled night sky as a symbol of his desire for open space and freedom from war.

Miró’s message

Miró’s aim was to rediscover the sources of human feeling,

to create poetry by way of painting, using a vocabulary of signs and

symbols, plastic metaphors (an implied similarity between two different

things), and dream images to express definite themes. He had a genuine

sense of humor and a lively wit, which also characterized his art. His

chief consideration was social, to get close to the great masses of

humanity, and he was deeply convinced that art can make a genuine appeal

only when returning to the roots of experience. In this respect

Miró’s attitude can be compared to that of Klee.

Miró was connected with the surrealists from 1924 to 1930.

Surrealism was a source of inspiration to him, and he made use of its

Joan Miró.

Reproduced by permission of

Archive Photos, Inc.

Harlequin’s Carnival

Career begins

After Miró completed his artistic education in Barcelona, he

produced portraits and landscapes in the Fauve manner, a style of

painting popular around 1900 that emphasized brilliant and aggressive

colors. He had his first one-man show in Barcelona in 1918 and later

that year he became a member of the Agrupacio Courbet, to which the

ceramist Joseph Llorenz Artigas belonged.

In 1919 Miró made his first trip to Paris, France, and thereafter

he spent the winters in Paris and the summers in Montroig. He met

members of the Dada group, an artistic and literary movement which

sought to expand the boundaries of conventional (having to do with the

common and the unoriginal) art. His first one-man show in Paris was held

in 1921 and his paintings of this period reflect cubist (having to do

with an artistic movement in the early twentieth century which used

geometric shapes) influences. His painting,

Montroig

(

The Olive Grove;

1919), for example, has a frontal, geometric pattern greatly influenced

by cubism.

Later Years

The Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted a major retrospective of Miro’s work in 1941, and following the end of the war, Miro’s popularity and influence spread across the United States, leading to his huge mural commission in Cincinnati in 1947.

Returning to live between France and Spain, Miro branched out into new media in the 1950s and 60s including printmaking and sculpture, while a series of retrospectives, awards and honours celebrated the depth and breadth of his legacy. By the time of his death in 1983, Miro’s place in art history as an international, Modernist master was already set.