Important Artworks

A conservatorship of his artworks and sketches was established with Rockwell’s aid at his house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and the Norman Rockwell Museum is currently open every day around the year. Below are a few examples of his most renowned pieces.

- Santa and Scouts in Snow (1913)

- Boy with Baby Carriage (1916; first Saturday Evening Post cover)

- Circus Barker and Strongman (1916)

- Gramps at the Plate (1916)

- Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (1916)

- People in a Theatre Balcony (1916)

- Tain’t You (1917; first Life magazine cover)

- Cousin Reginald Goes to the Country (1917; first Country Gentleman cover)

- Santa and Expense Book (1920)

- Mother Tucking Children into Bed (1921; first wife Irene as the model)

- No Swimming (1921)

- Santa with Elves (1922)

- The Love Song (1926, Ladies Home Journal)

- Doctor and Doll (1929)

- Deadline (1938)

“Norman F—ing Rockwell”

The first strains of “Norman F-cking Rockwell” are pretty strings; it sounds like the beginning of a Golden Age movie, or a ballet overture. Then the piano comes in, warm and unapologetic, with enthusiasm that feels like a Billy Joel tune. And then there’s Del Rey: “Goddamn, man-child,” she lilts. “Your poetry’s bad and you blame the news.” The title emphatically references the artist and author Rockwell, who was famous for illustrating quotidian scenes of mid-20th-century American life with a political conscience. But Del Rey seems less thrilled about her paramour’s art — although, in typical fashion, she seems to find joy in eviscerating the object of her complaints.

“The greatest”

One of the most directly nostalgic of Del Rey’s songs on Norman F—ing Rockwell, “The greatest” sees her looking back on recent history — both musical and political — as she bemoans the present. There’s a nod to Dennis Wilson, ill-fated drummer for the Beach Boys, and the paradise island of “Kokomo.” There’s a line about missing New York and its music scene, where she started, and the rock ‘n’ roll of an earlier era. There’s a mention of a 2018 missile scare in Hawaii, of changing weather in L.A., of Kanye West’s evolution from rapper to lightning rod of controversy, of the dire straits of the planet (“‘Life on Mars‘ ain’t just a song”). And then there’s her most millennial line yet: “The culture is lit, and if this is it, I had a ball / I guess that I’m burned out after all.” Her play on words turns the phrase on its head, skewering the youthful slang term “lit” and leaning into the nihilistic burnout instead.

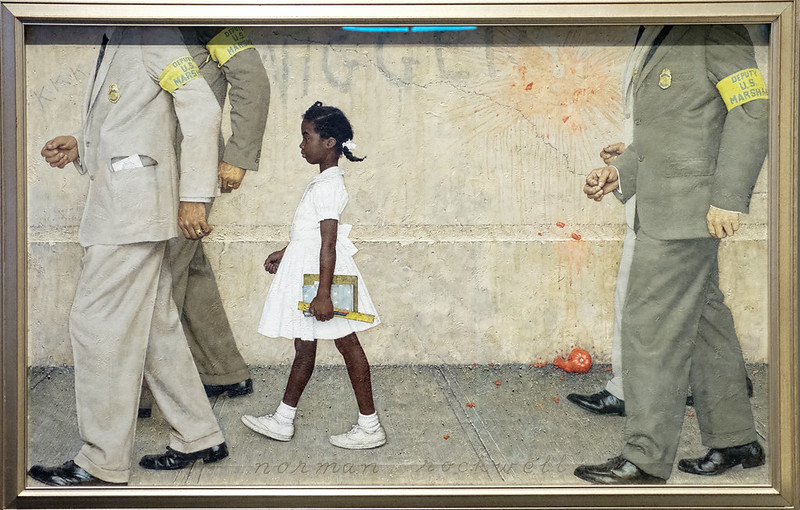

The Problem We All Live With

The Problem We All Live With stars Ruby Bridges, a 6-year-old African American girl, on her first day of class. Clutching school supplies and clad in a clean white dress, Bridges looks like any other student starting the first grade. What surrounds the young girl, however, is not typical. Flanked by U.S. Marshals and strolling before a wall covered in racist graffiti and a recently-thrown tomato, it is clear that Bridges’ experience is exceptional—and prompted by politics.

Historical Context

Following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, Bridges was one of a few students selected to start the desegregation process in New Orleans. Bridges was the only one of these children sent to William Frantz School. While her walk to the institution’s front doors was marred by a violent mob, Bridges did not buckle under pressure. In fact, “she showed a lot of courage,” Charles Burks, one of her Marshal escorts, said. “She never cried. She didn’t whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we’re all very very proud of her.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain

Bridges, however, attributes her mature handling of the situation not to bravery, but to childhood innocence. In 2011, she explained: “The girl in that painting at 6 years old knew absolutely nothing about racism—I was going to school that day. So every time I see that, I think about the fact that I was an innocent child that knew absolutely nothing about what was happening that day.”

Ruby Bridges with her portrait

Exploring the Painting

Rockwell made numerous artistic choices in The Problem We All Live With to emphasize the seriousness of the occasion. For instance, Ruby Bridges is wearing a bright white frock and sneakers, perhaps emphasizing her innocence in the face of adversity. This is highlighted by the offensive graffiti and thrown tomato surrounding her path to school.

Additionally, Rockwell made the choice of only showing Bridges’ face, while the depictions of the large, adult Marshals are cut off at the head. This is intended to underscore Bridges’ perspective of the situation, and stress her small size and young age.

“Bartender”

On “Bartender,” Del Rey kicks things off with a likely second Joni Mitchell reference: Mitchell’s 1970 album was called Ladies of the Canyon, itself a reference to women who live in L.A.’s famously creative Laurel Canyon area. Del Rey also name-checks Crosby, Stills and Nash, adding them to her long list of famous musicians she’s included in her music. Then there’s “Sometimes, girls just want to have fun” — which sounds a lot like “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” from Cyndi Lauper. And “the poetry inside of me is warm like a gun” feels like a call-out to the Beatles’ “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” All of these mentions weave together to form an idealized vision of her L.A., filled with ladies meditating in gardens and her incognito drives down the Pacific Coast Highway in a truck to see a bartender (“photo-free exits from baby’s bedside”) — although, as she notes, she’s only drinking Cherry Coke. (Recall that Del Rey has discussed her sobriety before.) “Bartender” deftly mixes the mythology of L.A.’s past with its present, positioning Del Rey’s struggle to keep love alive in the midst of contemporary fame as one more chapter in the story of Laurel Canyon artistry.

“Mariners Apartment Complex”

Released back in September 2018 as an early single, “Mariners Apartment Complex” sees Del Rey go folk. (She’s described the album to Billboard as “a folk record with a little surf twist,” which rings true now that it’s out.) Her breathiness is on full display, as is her confidence; “I ain’t no candle in the wind” suggests she’s not going anywhere. “You lose your way, just take my hand,” she insists. “You’re lost at sea, then I’ll command your boat to me again… I’m your man.” It’s a statement of purpose that sees Del Rey establish herself as much more than the lost ingenue character she previously inhabited in albums like Born to Die and Ultraviolence.

HE RECEIVED HIS FIRST COMMISSION AS A TEENAGER.

Rockwell’s career got off to a meteoric start. At age 14, this Manhattan native began taking classes through the New York School of Art. Within the next year, he joined the esteemed Art Students League, an organization which also boasts such icons as Georgia O’Keeffe and Maurice Sendak as alumni. Rockwell hadn’t even turned 16 when he received his first paid commission: a set of four Christmas cards, requested by a neighbor.

After that little milestone, the artist would tackle his first major assignment in 1912. At just 18, Rockwell was hired to paint a dozen illustrations for the children’s book Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature by Charles H. Caudy. This $150 gig helped set up a steady job as a staff artist and eventual art director for Boys’ Life magazine, where he’d begin working before the year was out.

THE ARMY USED HIS FOUR FREEDOMS SERIES AS AN EFFECTIVE FUNDRAISING TOOL.

Maia C. via Flickr //CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Maia C. via Flickr //CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On January 6, 1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave an historic State of the Union address. With the axis powers ominously looming, he held that everyone in the world deserved to enjoy freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

The president’s «four freedoms» address struck a chord with Rockwell. Inspired, he created a quartet of paintings that portrayed these ideals in action. Today, the artist’s Four Freedoms series is one of his best-known projects. After these paintings were published in The Saturday Evening Post, the government sent the originals on tour, enabling some 1.1 million people to view them. In the process, Rockwell’s four mini-masterpieces helped Uncle Sam sell nearly $133 million worth of war bonds.

“hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but I have it”

The album closer’s dirge-like, spare intimacy make it one of her most loaded songs on the album; producer Jack Antonoff shared that it was recorded on the first day they worked together, and it retains that immediacy. Over just a piano, Del Rey sings in lyrics that are oblique but specific, each noun a weighted term. First, there’s Slim Aarons, the famously chic mid-20th century American photographer of poolside scenes, whose aesthetic has become a mainstay of Instagram style. (Del Rey seems to feel that she’s not quite the model.) Then there’s Sylvia Path, feminist poet and author of The Bell Jar, who later committed suicide; Del Rey calls herself a “24/7 Sylvia Plath,” out on the town in a nightgown and “writing in blood on my walls” — a bold visual of the tortured artist experience. She calls out time spent with “Bowery Bums,” a name for residents of New York’s skid row, who gave her the “only love I’ve ever known.” But all this darkness is balanced out by the song’s titular suggestion, which takes itself from a Morgan Freeman quote in The Shawshank Redemption. Del Rey may be no stranger to struggles, but she maintains hope.

“California”

“California” doubles down on Del Rey’s fixation on the state (see: her mention of the “Santa Ana,” famously strong winds that whip through California). It also sees her calling in a reference to Joni Mitchell and her 1971 song “California,” which seems to serve as a direct inspiration. In that song, Mitchell sings of traveling around Europe — and “then I’m coming home to California… will you take me as I am, strung out on another man?” In her version, Del Rey has an answer: “If you come back to California, you should just hit me up / we’ll do whatever you want, travel wherever how far.” Mitchell mentions reading Rolling Stone and Vogue magazines; Del Rey promises “I’ll pick up all of your Vogues and all of your Rolling Stones.” It’s a conversation stretched out over the decades, one asking a question about the hospitality of the Golden State, the other answering graciously.

“F-ck it I love you”

Dreamy and languid, “F-ck it I love you” sees Del Rey in full reminiscence mode: “I moved to California but it’s just a state of mind / Turns out everywhere you go, you take yourself, that’s not a lie,” she recites in a rapid sing-song. (Del Rey moved from New York to Los Angeles in 2012.) She seems torn between two extremes — “Maybe the way I’m living is killing me… one day I woke up like, ‘Maybe I’ll do it differently’” could potentially be a reference to her history with alcohol: she’s discussed being sent to boarding school at 14 partially to get sober, and subsequently going to rehab. “It’s been nine years since my last drink,” she told GQ back in 2012. “I would drink every day. I would drink alone.” But the song is also about being muddled in love. When she sings “Dream a little dream of me,” it’s both a throwback to the 1931 pop standard tune and a plea for attention.

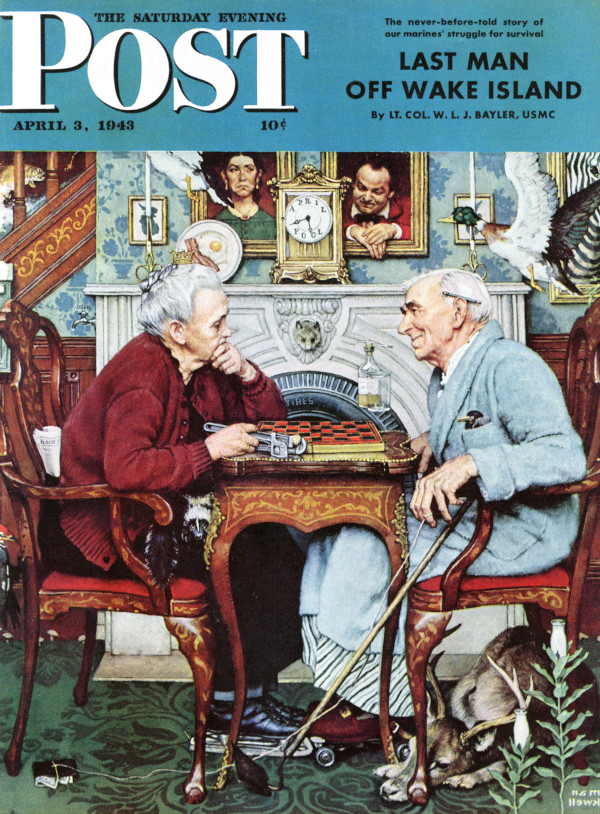

April 1943

April Fool, 1943Norman RockwellApril 3, 1943(Click to Enlarge)

April Fool, 1943Norman RockwellApril 3, 1943(Click to Enlarge)

- The principal April fooleries in the painting are.

- The trout, the fishhook and the water, all on the stairway.

- The stairway running behind the fireplace, an architectural impossibility.

- The mailbox.

- The faucet.

- Wall-paper upside down.

- Wallpaper has two designs.

- The scissors candlestick.

- Silhouettes upside down.

- Bacon and egg on the decorative plate.

- The April-fool clock.

- The portraits.

- Ducks in the living room.

- Zebra looking out of the frame.

- Mouse looking out of the mantelpiece.

- A tire for the iron rim of the mantelpiece.

- Medicine bottle and glass floating in the air.

- Fork in-stead of a spoon on the bottle.

- the old lady’s hip pocket;

- The newspaper in her pocket.

- Her wedding ring on the wrong hand.

- Buttons on the wrong aide of her sweater.

- Crown on her head.

- Stillson wrench for a nutcracker in her hand.

- Skunk on her lap.

- She is wearing trousers.

- She has on ice skates.

- No checkers on checkerboard.

- Wrong number of squares on checkerboard.

- Too many fingers on old man’s hand.

- Erasers on both ends of his pencil.

- He is wearing a skirt.

- He has a bird in his pocket.

- He is wearing roller skates.

- He has a hoe for a cane.

- Billfold on string tied to his finger.

- Milkweed growing in room.

- Milk bottle on milkweed.

- Deer under chair.

- Dog’s paws on deer.

- Mushrooms.

- Woodpecker pecking chair.

- Buckle on man’s slipper.

- Artist’s signature in reverse.

Norman Rockwell’s Art Style and Legacy

Norman Rockwell’s impact on American art has been subjected to justified revision, despite being praised by the likes of satirist George Grosz, and Willem de Kooning who lauded Norman Rockwell’s illustrations for their “incredible skill, clarity of touch,” and a populist intuition that was “so ubiquitous that he would be praised everywhere.”

Half-length photographic portrait of Norman Rockwell (1921); en:Underwood & Underwood, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

His photos, which are still mass copied, are considered now almost as paeans for a bygone era, according to The New York Times, which once stated that his work was on par with Mark Twain’s books in terms of importance to America’s self-image.

The Norman Rockwell Museum is dedicated to spreading “the capacity of visual imagery to change and reflect society” and has the world’s biggest collection of his work. “The Museum encourages social good via civic ideals of learning, respect, and inclusiveness, and is devoted to preserving freedom and respect through the timeless messages of compassion and generosity expressed by Norman Rockwell,” the museum’s mission statement states.

Freedom from Speech (between 1941 and 1945) by Norman Rockwell, as part of his Four Freedoms series; Norman Rockwell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During his lifetime, professional art reviewers disregarded Rockwell’s work. In the eyes of current critics, many of his works, particularly the Saturday Evening Post covers, which trend toward utopian or sentimentalized depictions of American life, are too sweet. The word “Rockwellesque” was coined as a result of this. As a result, some modern artists perceive

Rockwell’s work is often seen as kitsch, with other artists not considering him a “serious painter.” Some reviewers refer to him as an “illustrator” rather than an artist, which he didn’t mind because that’s what he identified himself with.

The sequence recounts the story of Ruby Bridges, a young black girl, who was escorted by white federal marshals while she walked to school past a wall vandalized by racist graffiti. When Bridges visited with President Barack Obama in 2011, this 1964 artwork was on exhibit there.

Commercial Success

The 1930s and ’40s proved to be the most fruitful period for Rockwell. In 1930, he married Mary Barstow, a schoolteacher, and they had three sons: Jarvis, Thomas and Peter. The Rockwells relocated to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939, and the new world that greeted Norman offered the perfect material for the artist to draw from. Rockwell’s success stemmed to a large degree from his careful appreciation for everyday American scenes, the warmth of small-town life in particular. Often what he depicted was treated with a certain simple charm and sense of humor. Some critics dismissed him for not having real artistic merit, but Rockwell’s reasons for painting what he did were grounded in the world that was around him. «Maybe as I grew up and found the world wasn’t the perfect place I had thought it to be, I unconsciously decided that if it wasn’t an ideal world, it should be, and so painted only the ideal aspects of it,» he once said.

Still, Rockwell didn’t completely ignore the issues of the day. In 1943, inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he painted the Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. The paintings appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post and proved incredibly popular. The paintings also toured the United States and raised in excess of $130 million toward the war effort. In 1953 the Rockwells moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where Norman would spend the rest of his life.

Following Mary’s death in 1959, Rockwell married a third time, to Molly Punderson, a retired teacher. With Molly’s encouragement, Rockwell ended his relationship with the Post and began doing covers for Look. His focus also changed, as he turned more of his attention to the social issues facing the country. Much of the work centered on themes concerning poverty, race and the Vietnam War.

April 24, 1926 Issue of The Saturday Evening Post

Puppy Love, a Norman Rockwell painting, appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post published April 24, 1926. This is another timeless favorite of Rockwell collectors, a classic for the ages.

The official title for this illustration is Boy and Girl Gazing at Moon, but I have always heard it referred to as Puppy Love, so that is why I named this article with the more popular alternate title. Other alternate titles for this painting include Little Spooners, First Love and Sunset.

This painting was Rockwell’s fourth cover for The Post in 1926. In 1926, there were ten Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post covers published.

This was also Rockwell’s 86th cover illustration out of 322 Rockwell painted for the Post. Rockwell’s career with the Post spanned 47 years, from his first cover illustration, Boy With Baby Carriage in 1916 to his last, Portrait of John F. Kennedy, in 1963.

The original oil on canvas painting, 24 x 20 inches or 61 x 51 cm, as of February 13, 2015 is part of the collection of The Norman Rockwell Museum of Massachusetts. A generous donation, indeed, by Bill Millis who had owned it since 1975.

This painting also appears in Rockwell commentary books. It appears:

- on pages 163 and 173 of Norman Rockwell 332 Magazine Covers by Christopher Finch,

- on page 36 of The Norman Rockwell Album,

- on page 58 of Norman Rockwell: America’s Best-Loved Illustrator,

- on page 53 of The Faith of America by Fred Bauer ,

- as illustration 217 of Norman Rockwell: Artist and Illustrator by Thomas Buechner and

- on page 103 of Norman Rockwell, A Definitive Catalogue by Laurie Norton Moffatt.

Yhe identity of the models is not known. The identity of the dog is also not known.

Pristine original copies of this magazine cover can sell for well over one hundred dollars on eBay. And to think it only cost five cents originally! Of course, it was mint condition then, too.

Other Norman Rockwell Paintings With Similar Themes

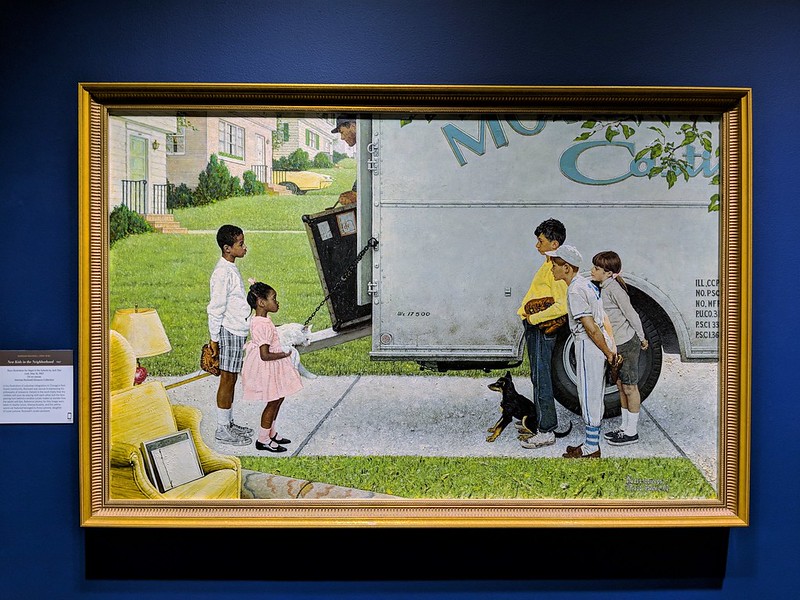

Norman Rockwell, “New Kids in the Neighborhood,” 1967

Three years after the publication of The Problem We All Live With, Rockwell revisited this theme. New Kids in the Neighborhood, another illustration for Look Magazine, features two groups of children: one black, and one white. Set in what appears to be a suburban neighborhood, the scene prominently features a moving truck. As the black children are positioned near the truck’s cargo, it can be inferred that they are the New Kids in the Neighborhood—and, judging by their curious expressions, the white children aren’t sure what to think.

Similar to the The Problem We All Live With—and in contrast to his past portrayals of kids—New Kids in the Neighborhood illustrates Rockwell’s interest in exploring the effects of racism on children.

ONE OF HIS PAINTINGS VISITED THE WHITE HOUSE IN 2011.

Created for Look magazine, the main subject of The Problem We All Live With (1963) is 6-year-old Ruby Bridges. On November 14, 1960, she began attending a newly integrated elementary school in New Orleans. Given the hostile environment, U.S. Marshals were instructed to escort her.

In 1975, The Problem We All Live With became the first painting to be bought by Stockbridge’s Norman Rockwell Museum. Since then, however, it’s seen a bit of travel. Between June and October 2011, the painting was put on display in a West Wing hallway at the White House. With President Barack Obama at her side, Bridges herself was able to go and view it there.

“Every time I see it, I think about the fact that I was an innocent child that knew absolutely nothing about what was happening that day,” said Bridges.

Final Years and Death

In the final decade of his life, Rockwell created a trust to ensure his artistic legacy would thrive long after his passing. His work became the centerpiece of what is now called the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge. In 1977, one year before his death, Rockwell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford. In his speech Ford said, «Artist, illustrator and author, Norman Rockwell has portrayed the American scene with unrivaled freshness and clarity. Insight, optimism and good humor are the hallmarks of his artistic style. His vivid and affectionate portraits of our country and ourselves have become a beloved part of the American tradition.»

Rockwell died at his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, on November 8, 1978.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Norman Rockwell

- Birth Year: 1894

- Birth date: February 3, 1894

- Birth State: New York

- Birth City: Brooklyn

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Norman Rockwell illustrated covers for ‘The Saturday Evening Post’ for 47 years. The public loved his often-humorous depictions of American life.

- Industries

Art

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

- Schools

- Art Students League of New York

- National Academy of Design

- Death Year: 1978

- Death date: November 8, 1978

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Stockbridge

- Death Country: United States

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Norman Rockwell Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/norman-rockwell

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: December 1, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Background[]

On September 18, 2018, during an interview with Zane Lowe, Del Rey explained the back story behind the title track:

- «So the title track is called «‘Norman Fucking Rockwell'» and it’s kind of about this guy who is such a genius artist but he thinks he’s the shit and he knows it and he like won’t shut up talking about it.»

On June 15, 2019, Del Rey posted a snippet of the song on her Instagram.

During an Instagram livestream on September 4, 2019, Del Rey revealed the track was originally titled «Bird World». She performed this version featuring verses different from the released version. Some of these unused lyrics and melodies would be reworked into «Dark but Just a Game», a song included on her following album, Chemtrails Over the Country Club. Del Rey would go on to say the title track is her favorite song on the album. It was the third song recorded with Jack Antonoff, after «Love Song» and «Hope Is a Dangerous Thing for a Woman like Me to Have — but I Have It».

The song was nominated for Song of the Year at the 62nd Annual Grammy Awards.

In mid-2022, the song went viral on TikTok, with hundreds of thousands of individual videos made using it, amassing millions of views.

“Venice B-tch”

Another early single, “Venice B-tch” is a play on words: this time she’s immersed herself in the hazy 1970s vibe of Venice Beach in Los Angeles. “Ice cream, ice queen, I dream in jeans and leather” — here’s classic Del Rey stringing together evocative nouns (maybe a callback to 2012’s “Blue Jeans”), each one building an impressionistic picture of an artist couple (“You write, I tour, we make it work”) ensconced in their cozy love affair. But there’s a dark side: “You’re beautiful and I’m insane, we’re American made,” she shares, and the song eventually devolves into a muddy, distorted-guitar-and-synth reverie for the rest of its 10-minute run. The psychedelia comes into focus with her bridge, where she repeats “crimson and clover” over and over, the title of a 1968 song from Tommy James and the Shondells.

Early Years

Born Norman Percevel Rockwell in New York City on February 3, 1894, Rockwell knew at the age of 14 that he wanted to be an artist, and began taking classes at The New School of Art. By the age of 16, Rockwell was so intent on pursuing his passion that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. He later transferred to the Art Students League of New York. Upon graduating, Rockwell found immediate work as an illustrator for Boys’ Life magazine.

By 1916, a 22-year-old Rockwell, newly married to his first wife, Irene O’Connor, had painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post — the beginning of a 47-year relationship with the iconic American magazine. In all, Rockwell painted 321 covers for the Post. Some of his most iconic covers included the 1927 celebration of Charles Lindbergh’s crossing of the Atlantic. He also worked for other magazines, including Look, which in 1969 featured a Rockwell cover depicting the imprint of Neil Armstrong’s left foot on the surface of the moon after the successful moon landing. In 1920, the Boy Scouts of America featured a Rockwell painting in its calendar. Rockwell continued to paint for the Boy Scouts for the rest of his life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Norman Rockwell?

His portrayal of the typical American was warm and upbeat, and he captured the regular routines and comely rituals of traditional American family life better than any other painter in the country’s history. Rockwell’s compositions were filled with wit and regard for his subjects, as well as a precision that made the spectator want to sigh and laugh at the same time, according to some. Painting during a time when abstract painting was becoming more fashionable, Rockwell was sure that his cheerful, uncomplicated images were superior to abstraction exploration’s self-indulgence.

What Was Norman Rockwell Known For?

Norman Rockwell, among the most renowned American artists of the 20th century, was sometimes regarded as a simple illustrator, his work being connected with Saturday Evening Post covers. Rockwell, a talented storyteller and astute observer of human nature, depicted America’s developing culture in little details and nuances, presenting scenes of ordinary people’s daily lives and offering a distinct and sometimes idealized interpretation of American identity. His images provided a relaxing visual refuge at an era of epoch-making transition that contributed to the development of contemporary American society.

Who was Norman Rockwell?

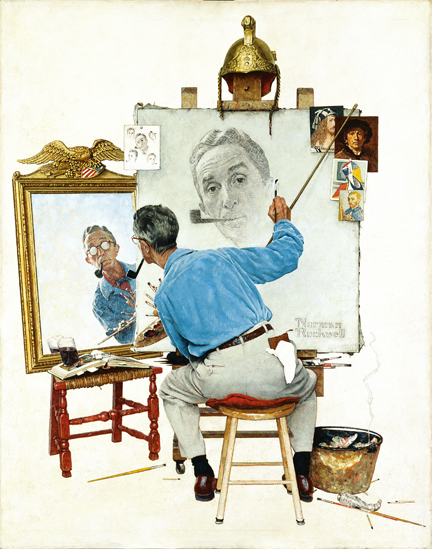

Norman Rockwell, “Triple Self-Portrait,” 1959

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City at the turn of the 20th century. As a child, he excelled as a painter, culminating in a job as a cover artist for Boys’ Life Magazine when he was just 18 years old.

Four years later, Rockwell would land a life-changing position at The Saturday Evening Post, a popular bi-monthly magazine. Over the span of 47 years, Rockwell completed 322 covers for the magazine, with most exploring quaint themes like childhood, coupledom, and the American workforce.

By the 1960s, Rockwell’s work remained popular with the public. In 1963, however, he left his job at The Saturday Evening Post and accepted a role at Look Magazine. It is during his time with Look that Rockwell’s interest in social justice emerged—and his old approach to art dissipated. “For 47 years, I portrayed the best of all possible worlds— grandfathers, puppy dogs—things like that,” Rockwell said in an interview at the age of 75. “That kind of stuff is dead now, and I think it’s about time.”

The year after he was hired by Look, Rockwell produced his most celebrated Civil Rights painting: The Problem We All Live With.

Lyrics[]

Album version

Goddamn man-child

You fucked me so good that I almost said, «I love you»

You’re fun and you’re wild

But you don’t know the half of the shit that you put me through

Your poetry’s bad and you blame the news

But I can’t change that and I can’t change your mood

Ah-ah

‘Cause you’re just a man, it’s just what you do

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

Yeah, you’re just a man, all through and through

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

Blue, blue, blue

Goddamn man-child

You act like a kid even though you stand six foot two

Self-loathing poet, resident Laurel Canyon, know-it-all

You talk to the walls when the party gets bored of you

But I don’t get bored, I just see it through

Why wait for the best when I could have you?

You, ooh

‘Cause you’re just a man, it’s just what you do

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

Yeah, you’re just a man, all through and through

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

Blue, blue

You make me blue

Blue, blue

Blue, blue, blue, blue

«Bird World» demo version

Hey, I heard you left town

Hey, heard you’re back around

Hey, hey

Heard you’re back in the bar again

Hangin’ out with your stupid friends

Playing with your guitar again

But I don’t fucking care

‘Cause you’re just a man, it’s just what you do

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

Yeah, you’re just a man, all through and through

Your head in your hands as you color me blue

You keep changing all the time

You’re changing your goddamn mind

You know you like to shine

But I don’t have a clue

‘Cause you’re just a man, it’s just what you do

Your head in your hands…

“Happiness is a butterfly”

“If he’s a serial killer, then what’s the worst / That could happen to a girl who’s already hurt? I’m already hurt,” Del Rey muses darkly on “Happiness is a butterfly.” It’s a powerfully sad line: a suggestion that she’s already hit rock bottom. In its title construction, “Happiness is a butterfly” echoes the Beatles’s “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” and this song is equally morose, melodic and surprising. Del Rey alludes to a relationship in flux: “Do you want me or do you not?” she wonders, name-checking Hollywood and Vine and “Laurel down to Sunset” — all L.A. streets — as she outlines the drama of their crumbling affair, her energy ramping up into a chorus that also works as an admonishment: “I said, don’t be a jerk, don’t call me a taxi!” In the end, Del Rey seems to say, love is fleeting and — like a butterfly — hard to capture; might as well take what she can get.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does The Problem We All Live With represent?

This painting is a form of visual commentary on racism and segregation in 1960s America. Rockwell depicted an actual event, taking artistic liberties to document the historic event in which segregation was abolished and Black children were being integrated in schools with white children.

Who is the girl in The Problem We All Live With?

The girl in the painting is Ruby Bridges. She was among the first African American students to be integrated in school when she was 6 years old.

What does the white dress symbolize in The Problem We All Live With?

There is a sense of innocence with the white dress that Ruby wears. Visually, the white dress is also a stark contrast to the young girl’s dark skin. This high contrast and draws the viewer’s eye to her.

THE GOLDEN RULE IS NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE UNITED NATIONS.

One of Rockwell’s most poignant paintings, 1961’s The Golden Rule, shows an international and multi-racial crowd standing in unison behind the words “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Rockwell later said that, prior to creating this piece, he’d “been reading up on comparative religion. The thing is that all major religions have the Golden Rule in common. … Not always the same words, but the same meaning.”

To celebrate the United Nations’ 40th anniversary, then-First Lady Nancy Reagan presented its Manhattan headquarters with a large mosaic version of Rockwell’s The Golden Rule. Nowadays, it’s a much-admired fixture there. “ virtually any hour, you will find tourists, delegates and diplomats marveling before it,” UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said.

Music video[]

| Music video | Information | |

|---|---|---|

|

Released | December 20, 2019 |

| Length | 14:06 | |

| Director | Chuck Grant | |

| Producer | Chuck Grant, Lana Del Rey | |

| Filmed | April, 2018 | |

| Location | Los Angeles, California | |

| Vevo views | 14+ Million views |

Background and Description

Del Rey shared a 2-minute clip of a music video for the track on August 31, 2019. It was shot by Chuck Grant and is a part of a 3-part video with «Bartender» and «Happiness Is a Butterfly». The video was originally set for release in October 2019. On December 17, 2019, Del Rey announced it would actually be released December 20, 2019. She shared another excerpt from the video the following day.

STEVEN SPIELBERG AND GEORGE LUCAS ARE BIG FANS.

Both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg own impressive collections of authentic Rockwell illustrations. Apparently, there’s a bit of a friendly competition going on as well. When Spielberg learned that Lucas owned a genuine Rockwell oil painting, he decided to up the ante. “I copied and got a Rockwell,” Spielberg said in 2010, “I went out and got a bigger Rockwell!”

Particularly impressive to the Star Wars creator is Rockwell’s mastery of visual narratives. “He was able to sum up the story and make you want to read the story, but actually understand who the people were, what their motives were, everything in one little frame,” Lucas said.

In July 2010, the two directors lent over 50 Rockwell paintings and sketches to the Smithsonian American Art Museum as part of a temporary exhibit called “Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg,” which ran until January 2011.

The Legacy of The Problem We All Live With

Today, Norman Rockwell remains primarily known for his charming Post covers. However, his Civil Rights-era paintings—especially The Problem We All Live With—are among his most powerful works of art.

As a testament to its significance, President Barack Obama had The Problem We All Live With temporarily installed in the White House in 2011. As he and Ruby Bridges gazed at the painting, the pair couldn’t help but marvel at the situation. “I think it’s fair to say that if it hadn’t been for you guys, I might not be here and we wouldn’t be looking at this together,” Obama, the country’s first African American president, remarked.

Later, Bridges reflected on his comment. “Just having him say that meant a lot to me and it always has. But to be standing shoulder to shoulder with history and viewing history—it’s just once in a lifetime.”

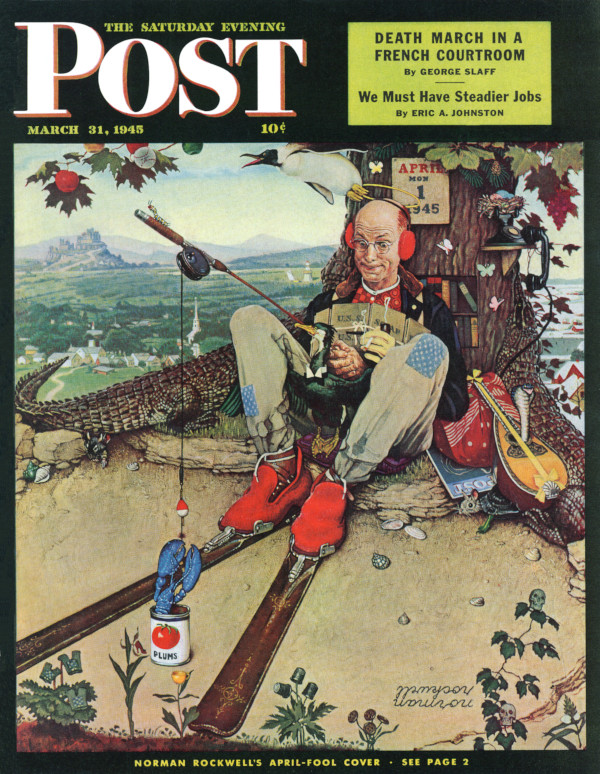

March 1945

April Fool, 1945Norman RockwellMarch 31, 1945(Click to Enlarge)

April Fool, 1945Norman RockwellMarch 31, 1945(Click to Enlarge)

- Apples on maple tree.

- Different-color apples.

- Baseball among apples.

- Pine boughs.

- Pine cone sh

- ould point down under bough.

- Horse-chestnut leaves.

- Grapes.

- April 1st comes on Sunday, not Monday.

- Penguins don’t fly.

- Halo.

- Nest on phone.

- Different-color eggs.

- Phone wire on wrong end of receiver.

- Different or wrong color butterflies.

- Books on tree.

- Castle in landscape.

- Lighthouse and ship.

- Earmuffs.

- Fur collar on velvet jacket.

- Two different designs on shirt.

- Shirt buttoned wrong way.

- Life jacket.

- Three hands.

- Cigarette and pipe used at same time.

- Collar and necktie on bird.

- Fly-casting reel on bait-casting rod.

- Cloth patches on waders.

- Rod upside down.

- Alligators as roots.

- Cobra in mandolin.

- Ribbon on mandolin.

- Post heading on wrong side of magazine.

- Snow scene.

- Horizons different on two scenes.

- Horns on mouse’s head.

- Animal head on turtle.

- You’re wrong; there are blue lobsters although they are

- extremely unusual freaks of nature.

- Tomato picture on plum can.

- House slippers on skis.

- Shells.

- Dutchman’s-breeches.

- Lady’s-slipper.

- Buttercup.

- Thimbleweed.

- Bachelor-buttons.

- Poison ivy.

- Signature upside down.

- Skis without backs.

- Lead sinkers on line should be below floater.

- Floater upside down.

- Red should be at top of floater in right position.