Related Questions

Did They Use An Original Jackson Pollock Painting In Ex Machina Or A Replica?

They would have used a copy of painting No 5 (1948) as the painting was sold by David Geffen, a Hollywood producer and film studio executive, for over $140 million USD in 2006. Geffen would have sold the painting long before the movie was produced, and no respectable art collector would place such a valuable work of art on a film set or studio.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Did They Use An Original Jackson Pollock Painting In Ex Machina Or A Replica?.

What Makes Jackson Pollock’s Art So Valuable?

Jackson Pollock was a brilliant and creative artist who was not afraid to try new techniques with art. He is known for being a founder of Abstract Expressionism and the gestural technique, also known as action painting. He never saw much success in his lifetime, but today his paintings fetch millions of dollars and are considered extremely valuable.

By clicking here, you can discover more by reading What Makes Jackson Pollock’s Art So Valuable?.

Understanding Jackson Pollock’s Paintings And His Art

Understanding that Jackson Pollock has absolute honesty in his paintings, he shows us his great technique and ability to use paint in ways that have never been used before. His paintings are very dimensional, so when you look at them in one way but get up close, you may see another way. He’s not trying to fool us in any way but just saying here, view it as you want to see it.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Understanding Jackson Pollock’s Paintings And His Art.

What was Pollock trying to do?

Blue poles is a painting, but not a conventional “easel painting”.

The footprint and the paint not running down the canvas tell us it was painted flat on the floor. It was not made with brushes or intended to represent identifiable things in the world.

Clearly, Pollock rejected that historical idea of painting – the small canvas on the easel on which paint is arranged to look like a real thing, like a landscape or a bowl of flowers.

You’ll hear Pollock was an “Abstract Expressionist”, which might sound like art-speak, but often names of historical art movements – those “isms” – are pretty literal: Conceptualism – its about concepts; Impressionism – it’s about an impression of a scene; Futurism – it’s about modernity; Hard-Edge Abstraction – oh, come on.

Unpack the phrase “Abstract Expressionism”: “Abstract”, well, this is certainly abstract art; “Expressionist” surely means it’s about expressing something; that is, an outpouring of something internal, such as an emotional or psychological state.

So, the lack of recognisable symbolism in Blue poles is deliberate. Much of Pollock’s work was about externalising his seemingly troubled internal states.

He was interested in Jungian psychoanalysis, which is based on ideas of a “collective unconsciousness” that all humans share.

Pollock’s erratic splashes of paint are intended to communicate to us the way he was feeling and thinking at the time he made the painting.

Even the blue “poles” on the canvas, which are the only ordered part of the painting, are smashed onto the surface, vertical but at different angles.

If you investigate further, you’ll find that Blue poles has quite a story behind it. According to Stanley Friedman, writing in in 1973, Pollock’s friend Tony Smith had arrived at Pollock’s studio and found him severely depressed, so Smith started the painting to distract the artist from his suicidal thoughts.

Both Pollock and Smith got extremely drunk during the painting session, and by the end of the evening they were smashing glass on the canvas and treading it in with their bare feet.

That’s where the footprint comes from. You can see shards of broken glass on the canvas if you see the actual painting. And no doubt there’s some blood in there somewhere.

(It’s worth noting that Smith takes no credit for Blue poles; he only claims to have started the painting process.)

Lindsay Barrett’s book, The Prime Minister’s Christmas Card (2001), discusses the controversy of when Blue poles was bought by the National Gallery of Australia. Barrett argues that in the early-1970s the painting came to symbolise for supporters the Whitlam Government’s progressive, politically modernist government, while detractors saw it as emblematic of the extravagant fiscal wastefulness of Whitlamism.

Whitlam himself defended the purchase, saying Blue poles was “a masterpiece”, and the Daily Mirror’s headline about drunks painting “our $1m masterpiece”, seemed to be mocking this endorsement by Whitlam.

The newspaper story accused Whitlam and other supporters of the purchase as creating an Emperor’s New Clothes scenario.

Влияние на современное искусство

Влияние «Голубых полюсов» выходит далеко за рамки истории искусства. Его влияние на современное искусство неоспоримо: многие художники черпают вдохновение в революционной технике и концептуальных идеях Поллока. Динамическая энергия и свобода, выраженные в «Голубых полюсах», оставили неизгладимый след в последующих поколениях художников, которые переняли и адаптировали принципы Поллока в своих произведениях. Слава картины также проистекает из ее способности выходить за рамки мира искусства и находить отклик у более широкой аудитории, которая ценит силу абстракции и безграничные возможности художественного выражения.

В заключение, книга Джексона Поллока «Голубые полюса: номер 11, 1952» известна по нескольким веским причинам. Его новаторская техника капельной живописи, монументальные размеры и величие, мастерский баланс хаоса и контроля, богатый символизм и глубокое влияние на современное искусство – все это способствует его беспрецедентному статусу в мире искусства. Будучи настоящим шедевром абстрактного экспрессионизма, «Голубые полюса» продолжают вдохновлять и провоцировать размышления, очаровывая публику своей завораживающей композицией.

Полезные ссылки:

https://www.jackson-pollock.org/blue-poles-number-11.jsphttps://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/pollock-blue-poles.html

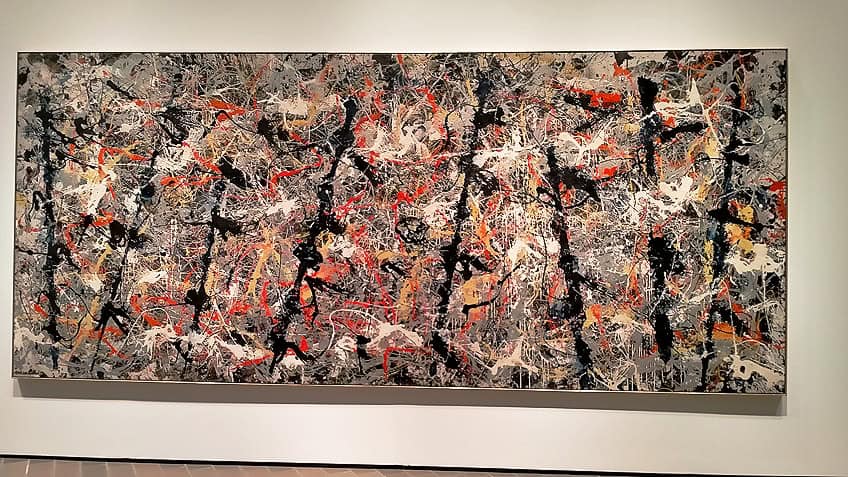

Number 17, 1951 – sold for $61.1 million, November 2021

Painted as part of a collection of black enamel painting created by Pollock towards the end of his life between 1951 and 1952, this square painting was auctioned for $61.2 million at Sotheby’s in November 2021. Measuring 148.6 x 148.6cm, Number 17, 1951 – along with the rest of this range – is somewhat unique among Pollock’s catalogue as being painted with just a single shade of paint – black enamel paint on canvas.

Number 17, 1951 was interpreted by many within the art world as indicating a return to Pollock’s earlier, more figure-based painting; and a departure from his densely-layered, ‘all over’ drip painting style. This painting set an auction record for a Jackson Pollock painting with its sale.

Number 17 (1951)

Jackson Pollock and Blue Poles

| Artist | Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956) |

| Date Created | 1952 |

| Medium | Oil, enamel, and aluminum paint with glass on canvas |

| Genre | Abstract |

| Period/Movement | Abstract Expressionism |

| Dimensions (cm) | 212.1 x 488.9 |

| Series/Versions | Standalone work |

| Where Is It Housed? | National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia |

| What It Is Worth | Estimated at around 350 million USD, though the exact value can vary based on market conditions and provenance. |

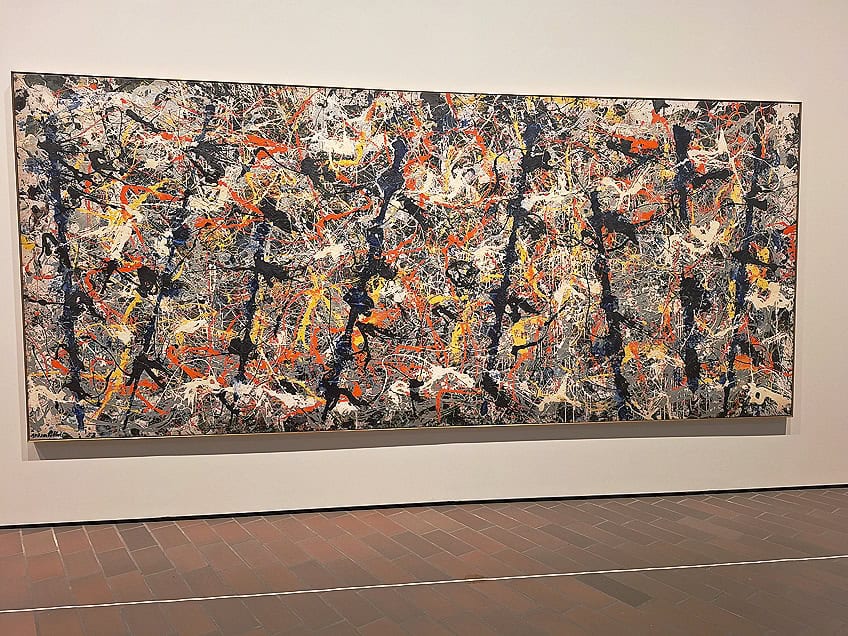

Blue Poles, also known as Number 11, 1952, is a signature piece by Jackson Pollock, an artist synonymous with Abstract Expressionism. Characterized by its distinctive technique and visually complex composition, the painting stands as a testament to Pollock’s revolutionary approach to art. Pollock’s method, often termed “action painting,” involved energetically dripping, splashing, and throwing paint onto a horizontal surface, marking a departure from traditional methods of brushwork and challenging conventional artistic norms of the time.

Pollock circa 1928; Smithsonian Institution, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The painting created waves not just in the art community but also in the broader cultural sphere, particularly when it was acquired by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973 amidst public debate concerning its artistic value and cost. The purchase brought the artwork into the international spotlight and cemented its status as a pivotal piece of 20th-century art. Blue Poles is now considered a cornerstone of Abstract Expressionism and a highlight of Jackson Pollock’s oeuvre, embodying the chaotic yet controlled energy that characterizes his most celebrated works.

Rise to Fame and Abstract Expressionism

Jackson Pollock’s rise to fame began in the 1940s as he developed a highly personal style that would come to define Abstract Expressionism. This movement, centered in New York, proposed a radical approach to art where the act of painting itself became the subject.

Characteristics of Pollock’s style included:

- Energetic drip and pour techniques

- Lack of a central focal point

- Use of non-traditional painting tools

The Genesis of Blue Poles

Blue Poles, also known as Number 11, 1952, exemplifies Pollock’s innovative action painting technique. He created the painting on a large canvas by dripping, pouring, and flinging paint in a controlled manner, a process intended to capture motion and emotion. This piece is a landmark in Abstract Expressionist art, reflecting Pollock’s intense engagement with the canvas that was laid out on the floor of his studio. The painting’s signature poles of blue paint traverse the canvas, creating a dynamic visual rhythm that distinguishes it from any other artwork of its time.

Blue Poles (1952), Jackson Pollock; SandwichCafe, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, via Flickr

Новаторская техника капельной живописи

Джексон Поллок известен своим уникальным методом рисования, известным как капельная живопись. Вместо того, чтобы использовать традиционные кисти, Поллок лил, капал и разбрызгивал краску прямо на холст, создавая динамичные и жестовые композиции. «Голубые полюса» иллюстрируют эту новаторскую технику: холст служит визуальной записью физических движений и эмоционального выражения Поллока. Использование этого нетрадиционного подхода не только бросило вызов традиционным представлениям о живописи, но и вызвало ощущение энергии и непосредственности, эффективно отражая суть внутреннего мира художника.

Discover six famous Jackson Pollock paintings that define how his artistic practice developed.

Guardians of the Secret, 1943

Guardians of the Secret was one of the most talked-about works in Pollock’s first solo show at the Guggenheim in New York in 1943. It represents many themes and influences the artist experienced throughout his life, including world mythology, African and Native American art, and prehistoric art. Pollock was exposed to these early art forms as a child, and he claimed to witness Indian rituals from an early age. Some historians believe that these experiences played an important role in the development of Pollock’s artistic process.

Also influenced by the compositions of Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso, Pollock painted Guardians of the Secret to feature abstracted forms. The male and female “guardians” at either side of the painting appear like Indian totems, Egyptian gods, or even chess pieces wearing African masks. A figure of a dog is painted at the bottom of the canvas in the style of ancient Egyptian tomb drawings. There’s also a tablet in the center of the composition which features hieroglyphic-like symbols. The blood-red rooster at the top perhaps represents the time Pollock lost the tip of his finger to an axe that was intended for a chicken.

Mural, 1943

Mural, painted in 1943, represents Pollock’s transition from his easel paintings and his signature drip canvases. Measuring nearly eight by 20 feet, this was Pollock’s first large-scale work, and it was commissioned for Peggy Guggenheim’s apartment. Legend has it that Pollock spent weeks staring at the blank canvas, complaining to friends that he had “creative block.” Finally, on New Year’s Day in 1944, he painted the entire canvas in one frantic burst of energy. (Despite this, the painting is still dated as 1943.) Pollock later told a friend of his vision for the piece: “It was a stampede… every animal in the American West, cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes. Everything is charging across that goddamn surface.”

Full Fathom Five, 1947

Full Fathom Five is one of Pollock’s earliest paintings made using his drip technique. Its surface is scattered with a number of random objects from Pollock’s studio, including nails, matches, cigarette butts, coins, and a key. The bottom layers of the painting were created using a brush and a palette knife, while the top layers were created by pouring from cans of black and silver house paint. “Like a seismograph,” noted writer Werner Haftmann. “The painting recorded the energies and states of the man who drew it.”

The title for Full Fathom Five was suggested by Pollock’s neighbor. It quotes part of The Tempest by William Shakespeare, when Ariel describes a death by shipwreck: “Full fathom five thy father lies / Of his bones are coral made / Those are pearls that were his eyes.”

Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950

Autumn Rhythm: Number 30 was one of the major works which appeared in Pollock’s 1950 solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. To create it, Pollock layed out the unstretched, 207 inch-wide canvas flat on the floor and constantly moved around it as he poured, dripped, flicked, and splattered the pigment onto it. Spontaneity was a critical element to Pollock’s work, but his free process didn’t mean he lacked control of his medium. He once was quoted saying, “I can control the flow of paint: there is no accident.”

Blue Poles, 1952

Blue Poles, (originally titled Number 11) is one of Pollock’s most famous works. It contains footprints and shards of glass throughout the canvas, signifying Pollock’s frenzied working method. In 1973, the National Gallery of Australia purchased Blue Poles for $1.3 million. Today, however, it has an estimated value of between $20 million and $100 million.

The Deep, 1953

During the 1950s, a dramatic shift occurred in both Pollock’s work and personal life. He began avoiding color and painted exclusively in black and white. Alcoholism began taking over his life and his productivity steadily declined. The Deep evokes Pollock’s inner battle. His signature drips are still featured, but they’re muted by layered brushstrokes of white paint. “It was not for nothing that white was chosen as the vestment of pure joy and immaculate purity,” said Wassily Kandinsky of the painting. “And black as the vestment of the greatest, most profound mourning and as the symbol of death.”

On the night of August 11, 1956, when Pollock was just 44 years old, he lost control of his car due to drunk driving and died. Edith Metzger also died in the car, and a third passenger, Ruth Kligman, was seriously injured.

Is it a masterpiece?

From an art historian’s point of view, whether or not Blue poles is a “masterpiece” depends mostly on how you regard Pollock and Abstract Expressionism. Certainly Pollock was a legend in his own lifetime, and Blue poles was produced at the height of his career.

In August 1949, LIFE magazine asked, “is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”, and in 1951, the year before Blue poles was painted, Vogue magazine used his paintings as a hip and happening backdrop to one of its fashion spreads.

The historical significance of Blue poles is indisputable; whether any artwork is “great” or a “masterpiece” is debatable.

Others have also considered different and interesting aspects of Blue poles. Richard Taylor, Director of the Materials Science Institute at The University of Oregon, has studied the painting as an example of chaos theory and fractals.

He argues that Blue poles is an example of a fractal pattern – that if we examine the drips closely, we see the basic form of the whole repeated.

In fact, Taylor actually claims that the aesthetic pleasure we might get from looking at Blue poles is a result of its chaotic forms, and the way that this resonates with a basic human preference for the chaos of nature over the order of culture.

It’s an interesting and, from an art theory point of view, potentially problematic argument – but it does illustrate how interesting interpreting art can be.

The Provenance and Acquisition

Blue Poles has traversed a significant journey in terms of ownership and has been the subject of a historic purchase that sparked substantial debate in the art world.

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles; SandwichCafe, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, via Flickr

Ownership and Exhibitions

Blue Poles was first owned by Ben Heller, a prominent New York art collector, who purchased it directly from Jackson Pollock. Prior to the acquisition by the Australian government, the painting was exhibited by the Sidney Janis Gallery. This abstract expressionist work left its imprint on numerous exhibitions, becoming a revered piece in international art circles.

Controversial Acquisition by Australia

In 1973, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra made a bold move under the governance of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. James Mollison, the gallery’s director, played a crucial role in the acquisition of Blue Poles for A$1.3 million, a record price that initiated a nationwide conversation. This controversial purchase, questioned by many at the time, was later seen as a visionary step for the cultural capital of Australia, as the piece has become one of the most celebrated in the gallery’s collection.

No. 14: Gray overview:

American born artist, Jackson Pollock, is considered to be one of the leading artists associated with abstract expressionism.

Pollock’s drip technique garnered him international praise and criticism. He is quoted in regard to his technique saying, “What’s the difference really between drawing directly on the canvas or in the space just above it? Everything and nothing, it turns out. That bit of distance relinquishes authorship and allows gravity and chance and life to play a part.”

This could be said to describe what would come to be known as automatism: spontaneous behavior that springs from the suppression of the conscious in favor of the unconscious. Certainly, this dynamic and unconventional approach to painting is hallmark of abstract expressionism.

Pollock’s critics accused him of being lazy and uncontrolled, but Pollock’s method of art embraces a deconstruction of the norms we once clung to. In the lines of Number 14: Gray, one sees the struggle between human intention and the unpredictable interference of life; that is, the space between the hand and the canvas.

The work, completed between 1947 and 1950, was realized with black enamel gently tossed over a canvas soaked in gesso (a white, glue-like substance). Normally, gesso is allowed to dry and used to prime the canvas, but Pollock applied the enamel over wet gesso, which lets it interfere with the absorption of the enamel: they bled together.

Pollock asked us, his audience, to surrender our own agency, not imposing ourselves onto the canvas but instead allowing the painting to be the subject acting upon us. In an interview with William Wright, he urged his viewers “not to look for but to look passively, and try to receive.”

For Pollock, humans, artists, no longer needed to look outward for subject matter, rather the subject matter comes from within in an expression of man trying to understand himself.

Символизм и интерпретативный потенциал

Любители искусства ценят то, что «Голубые поляки» служат визуальным катализатором интерпретации и самоанализа. Хотя абстрактный характер картины оставляет место для личной интерпретации, возникли различные теории относительно ее значения. Некоторые видят в вертикальных столбах, пронзающих холст, метафору хрупкости современной цивилизации и демонтажа традиционных ценностей. Другие интерпретируют хаотичную паутину красок как отражение сложности человеческих эмоций и экзистенциальных вопросов, которые преследуют всех нас. Эти многочисленные слои символизма и интерпретации продолжают делать «Голубые полюса» предметом восхищения и дискуссий как среди любителей искусства, так и среди ученых.