Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Джейн Хэвенс (1998). . Возвращение в Айову: мир Гранта Вуда — Ироническая линза Гранта Вуда: сатира . Университет Вирджинии . Проверено 8 января 2013 года .

- . Феникс . Бостон. 6 июня 2011 года Архивировано из 20 декабря 2013 . Проверено 8 января 2013 года .

- Кукуруза, Ванда. Грант Вуд, Регионалистское видение. Нью-Хейвен: Издательство Йельского университета, 1983, стр. 100

- Грэм, Нэн Вуд. . Художественный музей Фигге. Цифровая коллекция Гранта Вуда . Проверено 16 декабря +2016 .

- Адамс, Генри (октябрь 2010 г.). . Искусство и антиквариат . Проверено 8 января 2013 года .

- Дебора Соломон, «Gothic American» , The New York Times , 31 октября 2010 г., по состоянию на 7 января 2016 г.

- ^ Американская живопись, 1900–1970 (Библиотека искусств Time-Life) в твердом переплете — иллюстрировано, 1970 Роберт Уоллес и редакторы Time-Life Books.

| vтеГрант Вуд | |

|---|---|

| Картины |

|

| Разное |

|

| Связанный |

|

Grant Wood’s Timeless Legacy

In the final stretch of his life, Grant Wood painted captivating depictions of rural America, creating a legacy that now extends far beyond “American Gothic”. His unblemished portrayal of country life, detailed brushwork, and warm hues invite us into his childhood memories.

One prevalent theme in his later works is candid simplicity. His characters are everyday folks, engaged in everyday tasks, in everyday settings. This sincere simplicity resonated deeply with viewers then and continues to do so today. Even in his last painting, “Spring in the Country”, he made sure to leave us with an enduring taste of his childhood tranquility.

Wood passed away in 1942, but his spirit lives on through his art. His paintings serve as a window to America’s peaceful past, reminders of the serene landscapes and humble people that once filled its canvas. As we step back from his works, we’re left with a profound sense of nostalgia, peppered with appreciation for the simple, beautiful things in life. Now that’s a legacy to remember!

Происхождение [ править ]

В 1927 году Вуд получил заказ на создание витража в Мемориальном Колизее ветеранов в Сидар-Рапидс, штат Айова . Недовольный качеством отечественных стеклянных источников, он использовал стекло производства Германии. Местное отделение организации « Дочери американской революции» (DAR) пожаловалось на использование немецкого источника для мемориала Первой мировой войны , поскольку Германия была врагом США в той войне. Они выразили стойкие антинемецкие настроения в обществе, и другие жители Сидар-Рапидс также выразили протест немецкому источнику. В результате окно не было посвящено до 1955 года.

Говорят, Вуд описал DAR как «тех тори- девчонок» и «людей, которые пытаются создать в республике аристократию по рождению». Пять лет спустя Вуд написал « Дочерей революции», которую назвал своей единственной сатирой. Он подчеркнул контраст трех пожилых женщин в выцветших платьях в обрамлении героической картины « Вашингтон пересекает Делавэр» , которая, по иронии судьбы, была написана в Германии немецко-американским художником Эмануэлем Лойце . Вуд изобразил на моделях одежду своей матери, в том числе кружевной воротник и янтарную булавку, которую он купил для нее в Германии.

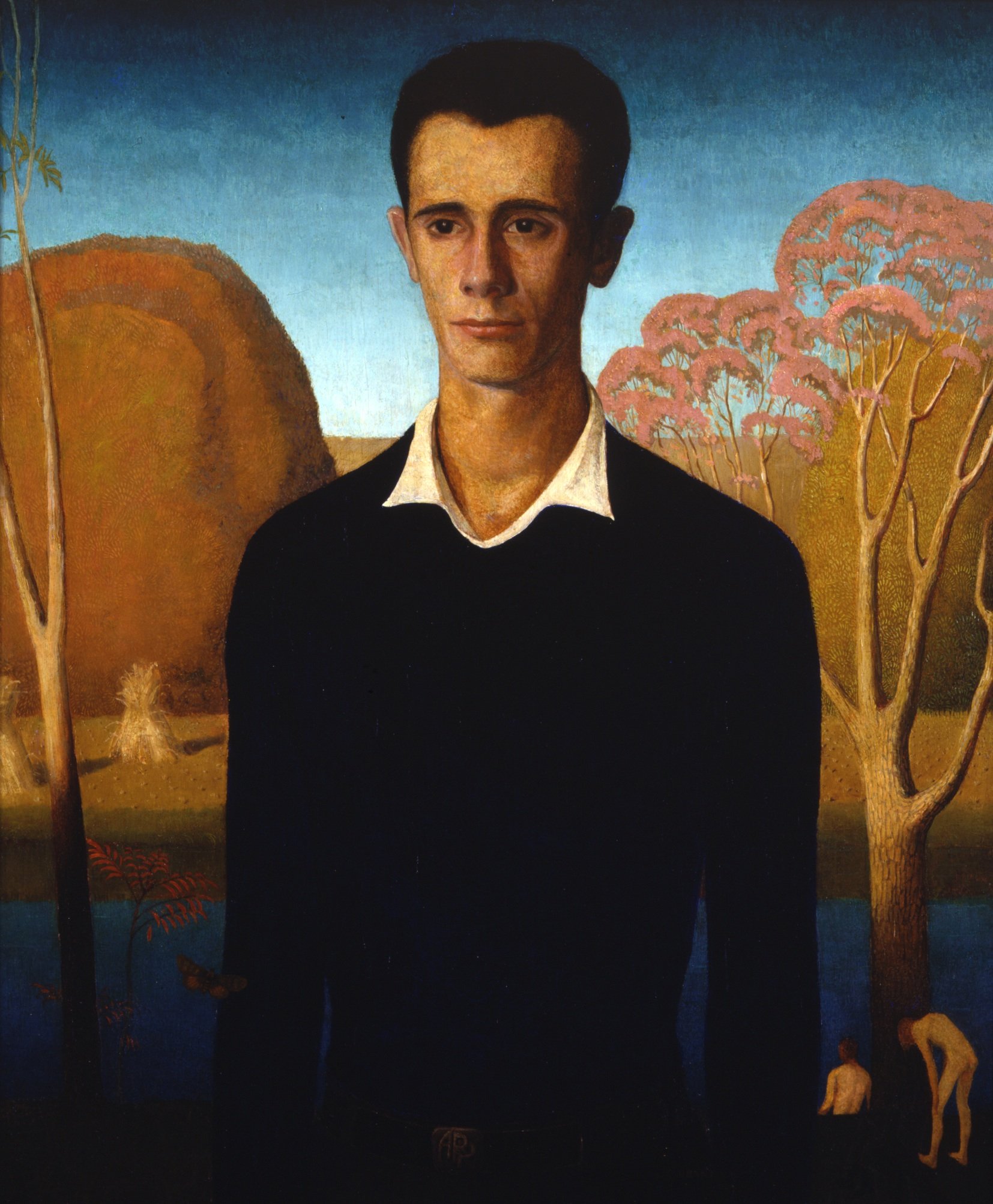

Arnold Comes of Age (1930)

“Arnold Comes of Age” certainly stirs a tale. Painted by Wood in 1930, this picture was originally a birthday gift for his young assistant, Arnold Pyle. Wood was known for his deep affection towards Pyle, whom he tutored.

This painting is not just a simple portrait. The young man, Arnold, gazes at the viewer with a look of both innocence and curiosity. The backdrop holds an important part of the story — two nude men enjoy a river swim. All this takes place in a tranquil countryside.

But sadly, this masterpiece was kept hidden for years. Around a decade after its inception, signs of aging started to show — discoloration, varnish loss and an overall deteriorated look. The bathing men, once clear figures, were now almost erased.

However, 1985 brought relief for this painting. The forgotten portrait underwent a full restoration. And with that, “Arnold Comes of Age” finally got its due recognition. It’s not just paint on canvas but a rich narrative of friendship, admiration and strong affection.

Arnold Comes of Age by Grant Wood, 1930, Wikimedia Commons

Творчество[править | править код]

Риджионализм

Имя Вуда тесно связано с американским течением, вошедшим в историю искусства под названием риджионализм, изначально распространившимся на Среднем Западе. Представители этого движения предпочитали изображать в реалистичной форме сцены из жизни американской глубинки в противовес европейскому абстракционизму. Вуд был одним из трех художников, более всего ассоциируемых с этим движением. Остальные, Джон Стюарт Кэрри и Томас Харт Бентон, благодаря покровительству Вуда получили места преподавателей в колледжах Висконсина и Канзаса.

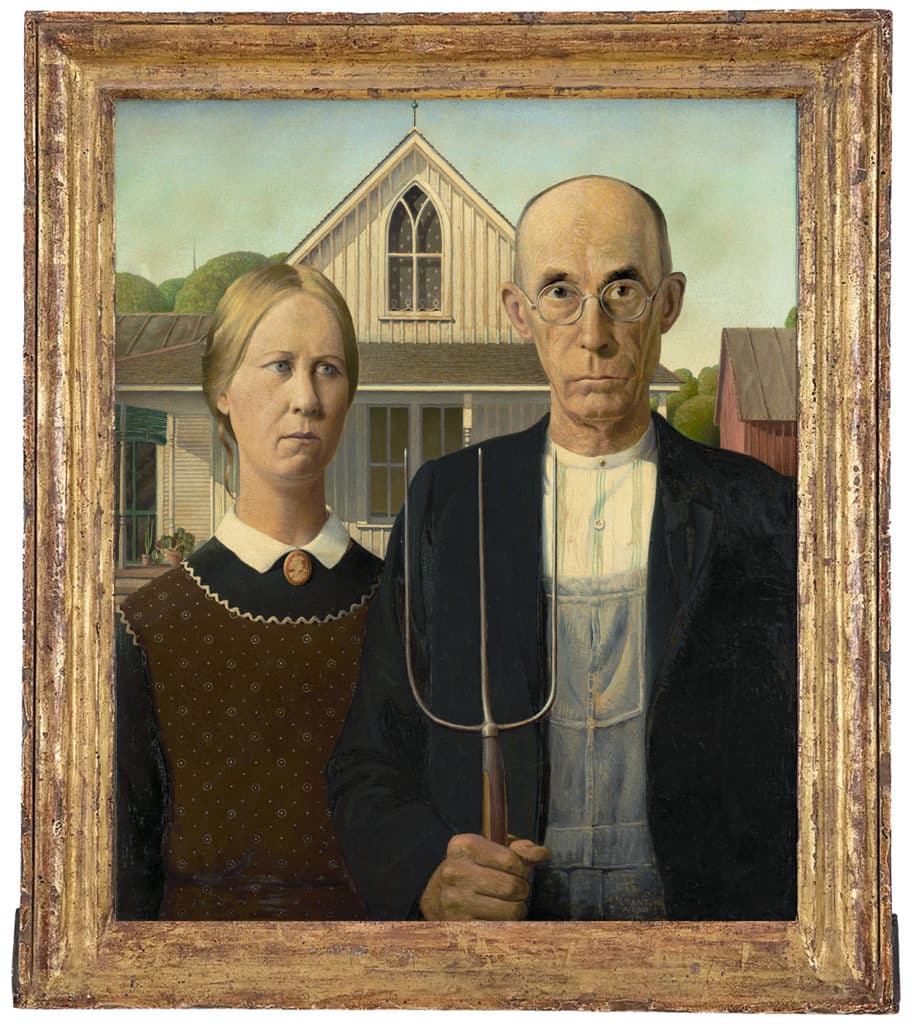

Картина «Американская Готика»

Самая известная картина Гранта Вуда «Американская Готика» (1930) — одно из наиболее узнаваемых произведений американского искусства. Вероятно, по уровню культурной знаковости эту картину можно без преувеличений сравнить с «Моной Лизой» да Винчи или с «Криком» Эдварда Мунка. Впервые она выставлялась Чикагском институте искусств в 1930 году, там же она хранится и сегодня. За эту картину Вуд получил премию в размере 300 долларов, и почти мгновенную славу. Образ стал расхожим, его используют и в рекламе, и в мультфильмах, и в карикатурах.

Самобытность и многогранность этого произведения, обеспечившие ему всемирную славу, прежде всего в самом, очень мощном визуальном образе, но и помимо этого, в возможности самых различных трактовок — вплоть до прямо противоположных. Вскоре после появления репродукции картины в газетах последовала негативная реакция общественности. Жители штата Айовы были разгневаны тем, как их изобразил художник. Художественные критики, благосклонно настроенные по отношению к данному произведению, например, Гертруда Стайн и Кристофер Морли, считали его острой сатирой на замкнутость и узколобость жителей маленьких провинциальных городков. Сам же Вуд отрицал подобную интерпретацию: с наступлением Великой Депрессии он видел в сельской Америке мужество и упрямство первопроходцев, пионерский дух и решимость в преодолении любых препятствий. Ещё одна трактовка предполагает смешение почтительности и легкой насмешки.

Вуд вдохновлялся неоготическим стилем небольшого особняка Элдона (южная Айова), особенно четко эти неоготические черты просматриваются в арочном окошке на втором этаже. Вуд решил изобразить этот дом, а на переднем плане людей, которые, по его мнению, могли бы в нём жить. На картине изображен фермер рядом со своей дочерью, старой девой. Художнику позировали его дантист Байрон МакКиби (англ. Byron McKeeby) и сестра Нэн (1900—1990). Именно сестра Вуда настаивала на версии, что на картине изображена дочь фермера, а никак не жена, так как ей хотелось думать о себе как о более молодой женщине. На женщине передник с рисунком колониальных времен, вилы в руке фермера призваны олицетворять тяжелый труд, позы и выражение героев картины заставляют думать о традиционном, патриархальном укладе жизни.

Композиционная строгость и проработанность деталей отсылают нас к Северному Возрождению, которое Грант особенно пристально изучал во время своих посещений Европы. Также он бережно относится и к достоверности в передаче атмосферы и деталей быта Среднего Запада, и это ключевая черта направления риджионализма.

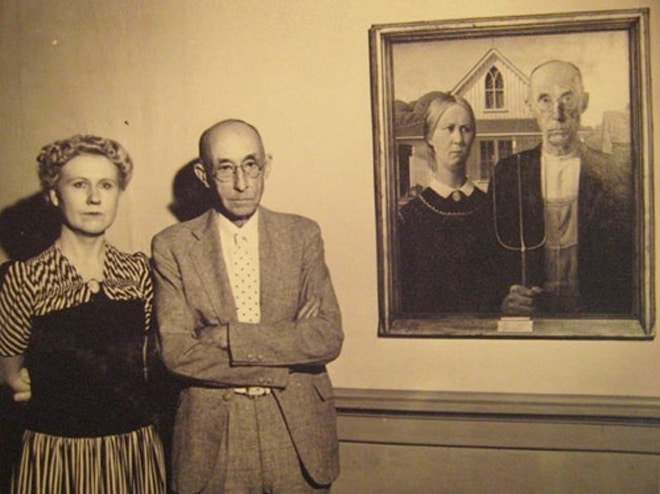

Who are the characters depicted in this painting?

Mystery surrounds the two figures in the painting: who are the woman with the worried look and the man with glasses staring at us? Are they a couple or friends? The man is older, so it is possible that we are looking at a father and his unmarried daughter.

The man is dressed in overalls but also in a black jacket, while the woman is wearing a piece of jewellery: they have made an effort to dress up, perhaps for the painter or to celebrate an important moment in their lives.

To create them, Grant Wood had his dentist Dr McKeeby and his sister Nan pose.

Grant Wood’s sister, Nan Wood Graham and Dr McKeeby next to the American Gothic painting

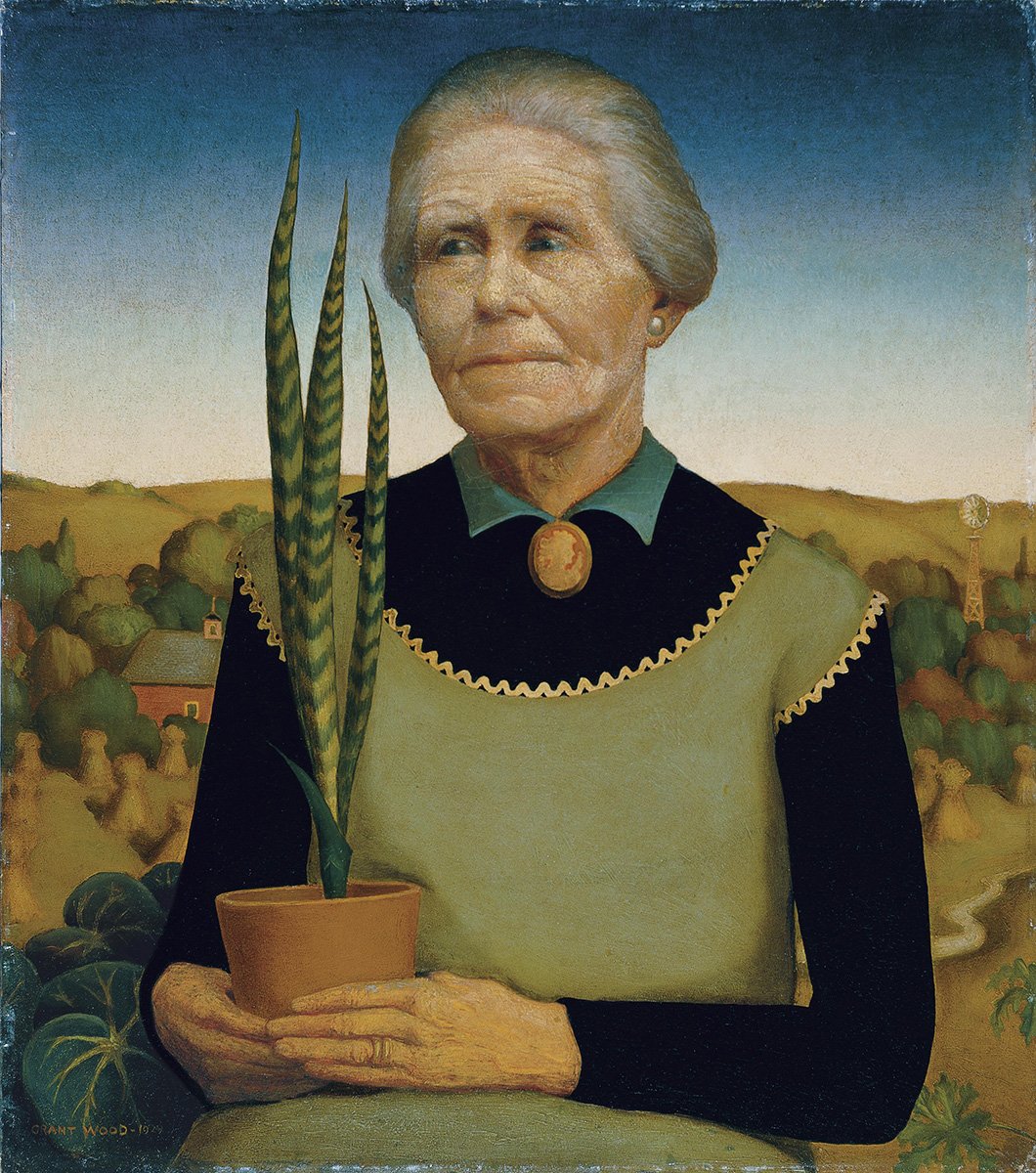

Woman with Plants (1929)

Grant Wood painted “Woman with Plants” in 1929. Just a year shy of his masterpiece, “American Gothic”. This piece features a half-length portrait of his mother, the steely and resolute Hattie Weaver Wood.

“Woman with Plants” is compelling in its simplicity. Wood places his subject front and center. Hattie dominates the canvas with her calm resilience. Commanding the scene alongside her is a snake plant. Hattie grips it tightly, its sharp leaves piercing the air like warrior’s swords. The plant’s details unravel the deep bond she shares with it, representing her personality — determined and unfaltering.

The synergy between the woman and the plant is uncanny. They mirror each other’s strength, forming a unified symbol of endurance emblematic of Wood’s works.

Ultimately, “Woman with Plants” is a loving tribute to Wood’s mother. Her strength, tenacity, and undying link to nature are beautifully captured. It signals the artist’s eternal respect, honoring the unwavering spirit that gave him life and paving the way for the ethos that would define his art.

Woman with Plants by Grant Wood, 1929, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art

Критика

Критики прокомментировали противопоставление этих женщин и мифической картины Джордж Вашингтон изображен в одном из своих подвигов военного времени. На основе биографии Триппа Эванса Грант Вуд, Жизнь (2010) Генри Адамс в своей рецензии говорит, что картина Вуда Дочери революции изображает не женщин, а мужчин: отцов-основателей переодевание фигуры, которые стоят перед воссозданной Вашингтон пересекает Делавэр. Эванс обсуждает предполагаемый гомосексуализм в своей книге, а также его увлечение тем, что Адамс описывает как «смену пола».

В своем обзоре книги Эванса Дебора Соломон считает, что он преувеличивает доводы в пользу Вуда как гомосексуалиста, и слишком сильно продвигает эту точку зрения при интерпретации своих работ. Она утверждает, что Вуда лучше назвать асексуалом. Соломон находит Вуда, преследуемого мертвыми, и говорит: «Он тосковал по компании мертвых и возвращался в прошлое в своих очаровательных и элегических картинах. Он заслуживает того, чтобы его помнили как одного из главных эксцентриков американского искусства». Сам Вуд назвал это «довольно гнилой картиной. Унесенный своим сюжетом».

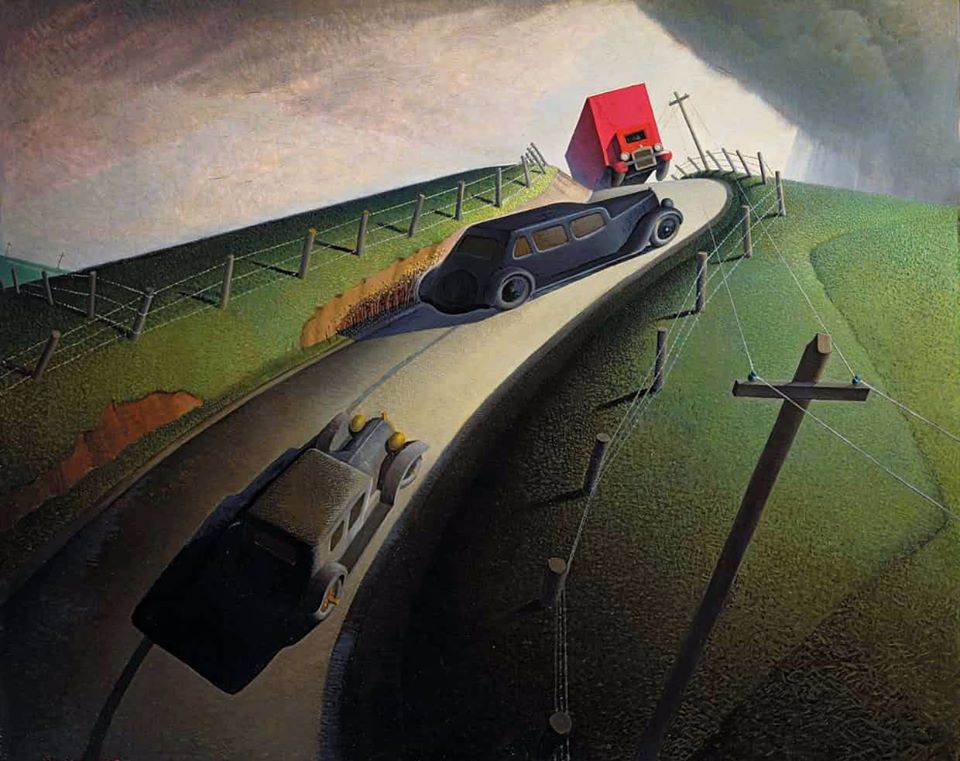

Death on the Ridge Road (1935)

“Death on the Ridge Road” portrays a disaster looming on a rural road. At its heart is a road, highlighted by parting clouds overhead that cast an eerie glow. The rest? Swallowed by darkness, giving an unsettling, trapped feel. It’s a suspenseful scene — stormy skies, two cars and a truck appear to be on a collision course. This ominous moment illuminates Grant Wood’s disdain for the intrusion of modernization into rural life.

Look closer. The slanted black car sprawls across the road, embodying reckless city culture. Its crash course? With the airborne truck, probably bearing farm goods, displaying the reckless speed of modernity that even rural folk must adopt to keep up. The other car, lingering in oblivion, reflects innocent bystanders thrust into this mess.

This bustling meander of city and rural life, according to Wood, is set to disastrously collide. Each element in this scene doesn’t merely represent a physical object, it gives voice to the fear of inevitable loss due to the unchecked march of technological progress. This isn’t just art, it’s a cry for a fading lifestyle and a testament to a time fading into dust.

Death on the Ridge Road by Grant Wood, 1935, Wikimedia Commons

Rise to Prominence

After World War I ended in 1919, Grant Wood took a position teaching art at a local Cedar Rapids middle school. The new income helped finance a trip to Europe in 1920 to study European art.

In 1925, Wood left his teaching position to focus on art full time. Following a third trip to Paris in 1926, he decided to focus on the common elements of life in Iowa in his art, making him a regionalist artist. Residents of Cedar Rapids embraced the young artist and offered jobs designing stained glass windows, executing commissioned portraits, and creating home interiors.

In the wake of national recognition for his paintings, Grant Wood helped form the Stone City Art Colony in 1932 with gallery director Edward Rowan. It was a group of artists who resided near Cedar Rapids in a village of whitewashed, tidy wagons. The artists also taught classes at nearby Coe College.

«Midnight Ride of Paul Revere» (1931).

Francis G. Mayer / Getty Images

In what context did Grant Wood paint this canvas?

Grant Wood (1891 – 1942) was an American painter known for his rural Midwest representations. After growing up on a farm in Iowa, he trained in the visual arts and then went to study in Europe in the 1920s. This trip allowed him to discover Flemish paintings, the German Renaissance and the New Objectivity, an artistic movement that developed in Germany and succeeded Expressionism.

In 1930, he painted American Gothic, at the very beginning of the Great Depression, the economic crisis that followed the stock market crash of 1929 and plunged the American rural world into great poverty.

Grant Wood, American Gothic – 1930 – 78 x 65,3 cm

The reception of the painting

Immediately after its premiere, the painting had a mixed reception. Iowans saw it as a caricature of rural life and were angry at being portrayed as ‘pinched, grimacing, fanatical puritans’. However, Grant Wood has always defended himself against this interpretation: for him the painting is a tribute to the rural population of the Midwest.

The artist’s sister, Nan Wood Graham, was made to look ugly by the painting, which led to a family dispute!

American Gothic was successful in the art world: exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the painting won a bronze medal and a $300 prize. The painting was featured in newspapers and quickly circulated throughout the country. In 1934, Time magazine ran a full-page reproduction of the painting, which helped make it famous.

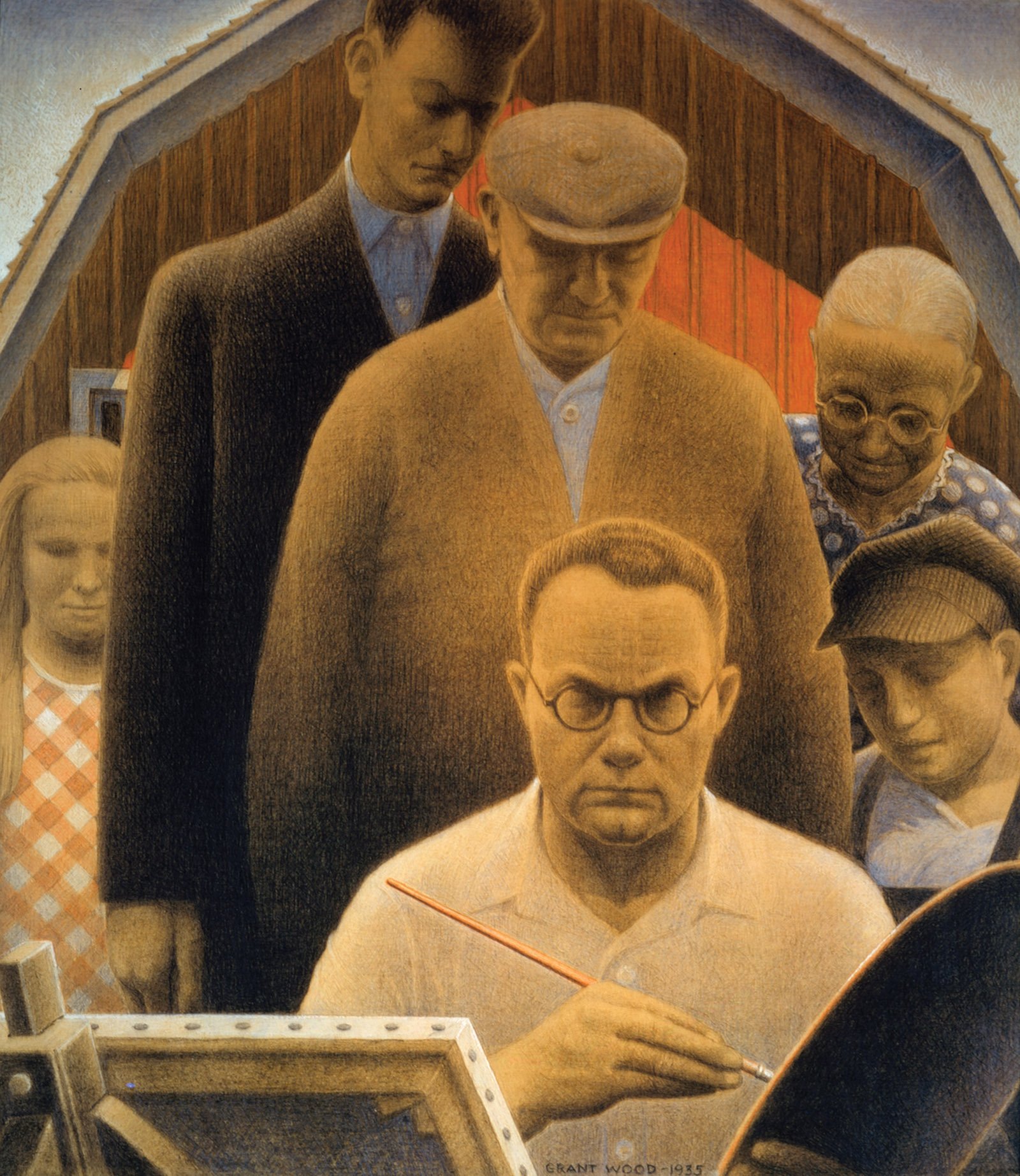

Return from Bohemia (1935)

“Return from Bohemia” was created in 1935 while Wood was in Paris. But don’t let that fool you — he wasn’t swayed by Parisian sophistication. Instead he used Paris to trigger his nostalgia for good old Midwestern charm.

The figures in the painting? That’s his audience and his subject. Deceptively simple, but look closer. Notice their clothes — a blend of old and new. Suggestive, isn’t it? The juxtaposition here is evident and intentional.

Picture this — Wood in a barnyard, paintbrush in hand. That’s the image he depicted for his autobiography’s jacket illustration. The book was his way of putting his Midwestern roots under the lens, an homage to his formative years on a farm, and his rebound from his foray into Impressionism.

See how the character’s eyes are downcast? Wood poses a question with this depiction — what does his homecoming truly mean? The figures don’t appear to be looking at the masterpiece but at the earth beneath. It seems they’re lost in thought, just like Wood during his return from a bohemian lifestyle. As plain as they appear, they speak volumes about Wood’s personal journey and the public’s perception of him.

In this intriguing piece, Wood masterfully blends his personal evolution with a commentary on cultural shifts. A return from Bohemia wasn’t just his journey home, but also a return to his artistic roots.

Return from Bohemia by Grant Wood, 1935, City of Davenport Art Collection