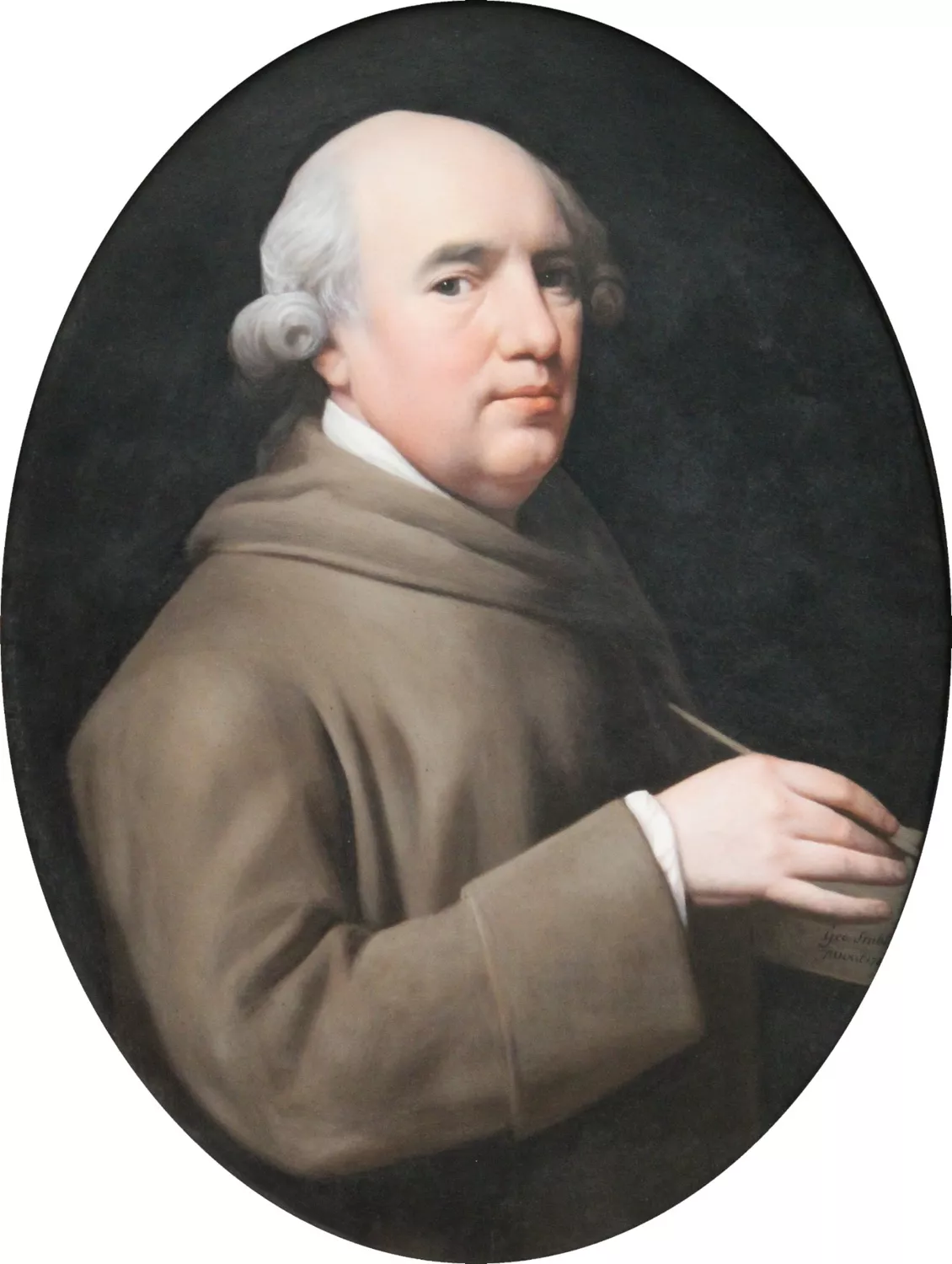

George Stubbs, Horse Painter

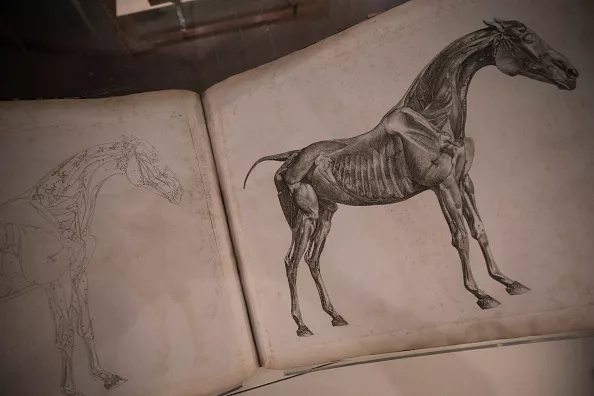

George Stubbs (1724-1806) was a self-taught artist who had an interest in anatomy from an early age. There is a story that a family friend lent him bones to draw as a child. He certainly studied anatomy and dissection in York where he lived for six years in the 1740s. He taught himself to etch and while there was commissioned to illustrate a book on midwifery.

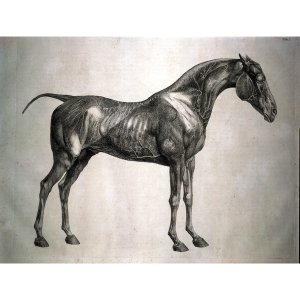

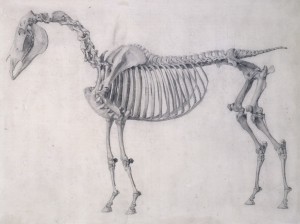

In 1758, Stubbs rented a farmhouse in Lincolnshire and spent 18 months studying dead horses. Gruesomely stringing the carcasses up on a system of pulleys, he injected their veins with wax to give them a lifelike appearance and proceeded to systematically study them in different positions, stripping off each layer of the body.

Отрывок, характеризующий Стаббс, Джордж

Графиня так устала от визитов, что не велела принимать больше никого, и швейцару приказано было только звать непременно кушать всех, кто будет еще приезжать с поздравлениями. Графине хотелось с глазу на глаз поговорить с другом своего детства, княгиней Анной Михайловной, которую она не видала хорошенько с ее приезда из Петербурга. Анна Михайловна, с своим исплаканным и приятным лицом, подвинулась ближе к креслу графини. – С тобой я буду совершенно откровенна, – сказала Анна Михайловна. – Уж мало нас осталось, старых друзей! От этого я так и дорожу твоею дружбой. Анна Михайловна посмотрела на Веру и остановилась. Графиня пожала руку своему другу. – Вера, – сказала графиня, обращаясь к старшей дочери, очевидно, нелюбимой. – Как у вас ни на что понятия нет? Разве ты не чувствуешь, что ты здесь лишняя? Поди к сестрам, или… Красивая Вера презрительно улыбнулась, видимо не чувствуя ни малейшего оскорбления. – Ежели бы вы мне сказали давно, маменька, я бы тотчас ушла, – сказала она, и пошла в свою комнату. Но, проходя мимо диванной, она заметила, что в ней у двух окошек симметрично сидели две пары. Она остановилась и презрительно улыбнулась. Соня сидела близко подле Николая, который переписывал ей стихи, в первый раз сочиненные им. Борис с Наташей сидели у другого окна и замолчали, когда вошла Вера. Соня и Наташа с виноватыми и счастливыми лицами взглянули на Веру. Весело и трогательно было смотреть на этих влюбленных девочек, но вид их, очевидно, не возбуждал в Вере приятного чувства. – Сколько раз я вас просила, – сказала она, – не брать моих вещей, у вас есть своя комната. Она взяла от Николая чернильницу. – Сейчас, сейчас, – сказал он, мокая перо. – Вы всё умеете делать не во время, – сказала Вера. – То прибежали в гостиную, так что всем совестно сделалось за вас. Несмотря на то, или именно потому, что сказанное ею было совершенно справедливо, никто ей не отвечал, и все четверо только переглядывались между собой. Она медлила в комнате с чернильницей в руке. – И какие могут быть в ваши года секреты между Наташей и Борисом и между вами, – всё одни глупости! – Ну, что тебе за дело, Вера? – тихеньким голоском, заступнически проговорила Наташа. Она, видимо, была ко всем еще более, чем всегда, в этот день добра и ласкова. – Очень глупо, – сказала Вера, – мне совестно за вас. Что за секреты?… – У каждого свои секреты. Мы тебя с Бергом не трогаем, – сказала Наташа разгорячаясь. – Я думаю, не трогаете, – сказала Вера, – потому что в моих поступках никогда ничего не может быть дурного. А вот я маменьке скажу, как ты с Борисом обходишься. – Наталья Ильинишна очень хорошо со мной обходится, – сказал Борис. – Я не могу жаловаться, – сказал он. – Оставьте, Борис, вы такой дипломат (слово дипломат было в большом ходу у детей в том особом значении, какое они придавали этому слову); даже скучно, – сказала Наташа оскорбленным, дрожащим голосом. – За что она ко мне пристает? Ты этого никогда не поймешь, – сказала она, обращаясь к Вере, – потому что ты никогда никого не любила; у тебя сердца нет, ты только madame de Genlis (это прозвище, считавшееся очень обидным, было дано Вере Николаем), и твое первое удовольствие – делать неприятности другим. Ты кокетничай с Бергом, сколько хочешь, – проговорила она скоро.

Stubbs and Romanticism

Whistlejacket is treated like an individual by Stubbs, but he also turns into a Romantic hero. The lack of saddle or bridle, or the presence of humans, gives him a sense of freedom and wildness. The dramatic pose, the flowing mane and tail, and the slightly wild look in his eye create a narrative of drama and tension.

Stubbs produced many images of wild animals, including a series of seventeen paintings showing a horse being attacked by a lion. These were allegedly based on an event the artist witnessed in North Africa while returning from Italy. He certainly made sketches of lions which were kept at the Tower of London. In many of the versions, the horse is an Arabian with similar coloring to Whistlejacket.

A Horse Called Whistlejacket

Horse racing became very popular among the elite in the 18th century. Successful horses like Hambletonian and Gimcrack had celebrity status and were frequently recorded on canvas. Whistlejacket was certainly not the most famous nor the most successful racehorse that Stubbs painted. Foaled in 1749, he won races in the north of England but lost two out of three times when he ran at Newmarket in 1756 and was sold on by his owner. He subsequently won a race worth 2000 guineas (the equivalent of over £400,000 today) at York in 1759 and was then put out to stud.

Part of Whistlejacket’s appeal has to do with aesthetics. With coppery coloring and lighter mane and tail, he resembled the original, wild Arabian horses he was descended from through his grandfather, the Godolphin Arabian. He was also notoriously difficult to handle, which might explain his short racing career and Stubbs’ choice to show him in a levade, poised on his hind legs, rather than in a more static stance.

Приложения

Библиография

-

Авторитетные записи :

- ( )

- Словарь Бенези , Критический и документальный словарь художников, скульпторов, рисовальщиков и граверов всех времен и стран , т. 13, Париж, выпуски Gründ,Январь 1999 г., 4- е изд. , 13440 с. ( ISBN 978-2-7000-3023-5 и , LCCN ) , стр. 326-327

- Моррисон, Венеция. Джордж Стаббс. Суть его работы. Париж, Succès du Livre, 2003. 192 страницы.

- Перевод английской статьи Википедии

- Теренс Доэрти: Анатомические работы Джорджа Стаббса , Лондон, Секер и Варбург, 1974. ( ISBN 0-436-12990-6 )

- Бэзил Тейлор, Отпечатки Джорджа Стаббса , Лондон, Фонд Пола Меллона для британского искусства, 1969.

|

Лошади в искусстве |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Общий | Конный портрет • Список конных портретов • Конная статуя • Пегас в искусстве | ||||||

| Рисунок и живопись |

|

||||||

| Скульптура |

|

||||||

| Другой | Солнечная колесница Трундхольма • Конь Даларны • Всадник в шахматной игре • Мозаика коней Карфагена |

Paintings by George Stubbs

George Stubbs (1724 – 1806) was an English painter who is best remembered by his masterful paintings of horses and other animals. He was largely a self taught painter, though he briefly studied with Hamlet Winstanley. During the 1750s, Stubbs dissected many horse specimens in order to study their anatomy and create accurate representations of them within his paintings. Finally, in 1766, he published a portfolio of his extensive equine studies which was titled as The Anatomy of the Horse. His most famous painting is Whistlejacket and is a highly rendered painting of a beautiful horse against a plain background.

George Stubbs’s paintings in chronological order:

| Racehorses Belonging to the Duke of Richmond Exercising at Goodwood, 1761 | Horse Attacked by a Lion, c.1762 | Mares and Foals in a Wooded Landscape, 1762 |

| The Grosvenor Hunt, 1762 | Whistlejacket, 1762 | Zebra, 1763 |

| Cheetah with two Indian servants and a deer, 1765 | Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath, with a Trainer, a Stable lad, and a Jockey, 1765 | Horse Attacked by a Lion, 1765 |

| Lion Attacking a Horse, 1765 | Lord Grosvenor’s Arabian Stallion with a Groom, c.1765 | Mares and foals are anxious before a looming storm, 1765 |

| Frontal view of the skeleton of a horse, study No. 10 from ‘The Anatomy of the Horse’, 1766 | Mares and Foals in a River Landscape, 1766 | Portrait of a Huntsman, 1768 |

| The Hunters leave Southill, 1768 | Colonel Pocklington with His Sisters, 1769 | Mares and Foals in a Mountainous Landscape, 1769 |

| A Horse Frightened by a Lion, 1770 | Lady Reading in a Wooded Park, 1770 | The Moose, 1773 |

| Portrait of a Monkey, 1774 | Pumpkin with a Stable Lad, 1774 | Mares and Foals under an Oak Tree, 1775 |

| Portrait of Isabella Saltonstall, c.1775 | Portrait of John Nelthorpe as a child, c.1775 | Portrait of Richard Wedgewood, c.1775 |

| Self-Portrait, c.1775 | Sir John Nelthorpe, 6th Baronet out Shooting with his Dogs in Barton Field, Lincolnshire, 1776 | A Bay Hunter With Two Spaniels, 1777 |

| John and Sophia Musters riding at Colwick Hall, 1777 | Sleeping Leopard, 1777 | Brown and White Norfolk or Water Spaniel, 1778 |

| Pavian and Albino Makake, c.1780 | Self-Portrait, 1781 | Viscount Gormanston’s White Dog, 181 |

| Harvest, 1785 | Park Phaeton with a Pair of Cream Pontes in Charge of a Stable Lad with a Dog, 1785 | A Saddled Bay Hunter, 1786 |

| Lord and Lady in a Phaeton, 1787 | A Foxhound, Ringwod, 1792 | Hound and Bitch in a Landscape, 1792 |

| Red Deer Stag and Hind, 1792 | A Grey Horse, 1793 | Laetitia, Lady Lade, 1793 |

| Prince of Wales Phaeton, 1793 | Soldiers of the 10th Dragoon Regiment, 1793 | Two Bay Mares And a Grey Pony In a Landscape, 1793 |

| William Anderson with two saddle-horses, 193 | Baronet, 1794 | Josiah Wedgwood, 1795 |

| Freeman, the Earl of Clarendon’s Gamekeeper, With a Dying Doe and Hound, 1800 | A Chestnut Racehorse | A Grey Stallion In A Landscape |

| A Water Spaniel | Brood Mares and Foals | Cattle by a Stream |

| Diagram from The Anatomy of the Horse | Diomed | Earl Grosvenor’s Bandy |

| Eclipse | Five Brood Mares | Godolphin Arabian |

| Hambletonian | Hay Makers | Horse Devoured by a Lion |

| Marske Horse | Melbourne and Milbanke Families | Messenger Horse |

| Snap With Trainer | Spanish Pointer | Study of a Fowl, Lateral View, with skin and underlying fascial layers removed, from ‘A Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body with that of a Tiger and a Common Fowl’ |

Research the anatomical drawings of George Stubbs (1724-1806) and consider how these inform Stubbs’s finished pieces.

George Stubbs, an engraving from The Anatomy of the Horse.Published in London, England, AD 1766 (British Museum)

George Stubbs was an exceptional English painter who is most known for his paintings of horses. The son of a prosperous tanner, Stubbs was briefly apprenticed to a painter but was mainly self-taught. He was interested in anatomy from an early age.

Stubbs studied anatomy at the York Hospital (c.1745) and while there he illustrated Dr John Burton’s Essay towards a Complete New System of Midwifery (1751), from drawings of dissections he had helped with. He then taught himself himself how to engrave them and these 18 small etchings published anonymously were his first exercises in printmaking.

Whistlejacket, about 1762, George Stubbs. The National Gallery

It was probably in 1756 that Stubbs began intensive study of the anatomy of the horse which he had planned during his time at York Hospital (c. 1745) but postponed until he could devote himself fully to the project.

For about 18 months he worked in a rented farmhouse at Horkstow, Lincolnshire, near tanneries that supplied him with dead horses. He devised tackle for hauling them into lifelike attitudes and stripped away layers of skin and muscle to the skeleton, making drawings and notes at every stage. He was assisted by Mary Spencer, his common-law wife.

Finished study for ‘The First Anatomical Table of the Skeleton of the Horse’, 1756-1758 (Royal Academy)

This conjures up some grim visions but Stubbs was driven by his desire to gain the knowledge needed to paint living horses and his upbringing as the son of a tanner, combined with the hospital experience, is likely to have given him the confidence, nerve and skills to tackle the project

When he published The Anatomy of the Horse (1766), he described himself on the title-page as ‘George Stubbs. Painter’. The 42 surviving drawings (London, RA) include working drawings and meticulous finished drawings which he used to create the etched plates for publication.

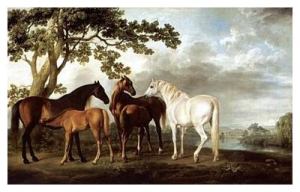

GEORGE STUBBS (1742-1806)‘Mares and Foals in a River Landscape’, 1763-68 (oil on canvas)

The Anatomy of the Horse became a major work of reference for naturalists and artists and Stubbs soon established a reputation as the leading painter of horse portraits with numerous commissions. His horse pictures include hunters and racehorses as well as more informal pictures of horses and foals in landscape settings. Stubbs also painted dogs and wild animals as well as human portraits, often of the horses’ owners.

Stubb’s pictures stand out because the horses (and other animals) he depicts are beautiful and realistic. His extraordinary knowledge of anatomy enabled him to capture natural postures and muscle tone as well as the horses shining coats, grace and strength. His exceptional understanding of their muscular and skeletal structure enabled him to depict horses realistically whether formally posed with their owners, rearing up or quietly grazing. He gained his insights from dead horses but the the horses he painted always look alive – as if they might flick a tail, toss their heads or gallop away any moment.

Sources

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Oxford Art Online

Works (selection)

A Lion Attacking a Horse , 1770, Yale University Art Gallery

- Hound Coarsing a Stag , around 1762, Philadelphia Museum of Art , Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Gimcrack with a groom on Newmarket Heath , 1765, private collection.

- A Cheetah and a Stag with Two Indian Attendants , 1765, Manchester Art Gallery , Manchester, England.

- The Milbanke and Melbourne Families around 1769, National Gallery , London.

- Whistlejacket , National Gallery , London.

- Newmarket Heath, with a Rubbing-down House , c.1765, Yale Center for British Art.

- Horse Frightened by a Lion , Walker Art Gallery , Liverpool.

- Lions and a Lioness with a Rocky Background , 1776, Victoria and Albert Museum , London.

- The Marquess of Rockinham’s Arabian Stallion , 1780, Scottish National Gallery , Edinburgh.

- Horse in the Shade of a Wood , 1780, Tate Gallery London.

- Leopards at Play , 1780, Tate Gallery London.

- Portrait of a Young Gentleman Out Shooting , 1781, Tate Gallery London.

- A Gentleman driving a Lady in a Phaeton 1787, National Gallery, London.

- The Prince of Wales’s Phaeton , 1793, Royal Collection Trust.

- William Anderson with two Saddle-Horses , 1793, Royal Collection Trust.

A Portrait of a Horse

Stubbs combined his knowledge of anatomy with his powers of observation to create a painting which was lifelike and characterful – a true portrait. Whistlejacket poses with his head slightly turned towards us, just as a human portrait might be. A look of wariness, perhaps even fear, is clearly visible in his eye, picked out by the white highlight.

Although the painting looks crisply outlined and precisely finished from a distance, up close the brushwork is loose, the lines softened, the mane merely sketched in. This broad handling adds to the sense of life and naturalism.

The dramatic stance creates the impression of a moment of captured time and allows Stubbs to show raised veins and active muscles, emphasizing that this is a living, breathing animal. At the same time, he shows the individual markings, like the white sock and forehead flash, which make Whistlejacket recognizable.

The first biography of the artist contains the story that as he was finishing the canvas in the stables, Whistlejacket was led past and reacted violently to the sight of the painting, thinking that it was a rival stallion. It may not be true. Roman writer, Pliny, has a similar anecdote about Greek artist, Zeuxis, who painted grapes so realistically that birds tried to peck at them. However, there is no doubting the realism of Stubbs’ portrayal of Whistlejacket.

биография

Стаббс родился в Ливерпуле , в семье торговца кожей. Его начало мало известно, по крайней мере, до тридцати пяти лет, и, по сути, оно связано с записями, сделанными художником Озиасом Хамфри незадолго до смерти художника. Он работал до пятнадцати лет в семейном бизнесе, а затем, после смерти своего отца в 1741 году , он ненадолго поступил в ученики у Гамлета Уинстенли , художника и гравера в Ланкашире, который он быстро оставил из-за своей работы переписчиком. В конце 1740- х годов он стал портретистом на севере Англии, изучая анатомию в больнице графства Йорк (между и 1751 годами ). С раннего возраста он был увлечен анатомией, и одной из его первых работ была коллекция иллюстраций к родам для книги доктора Джона Бертона (1701-1771), « Эссе о совершенно новой системе акушерства» в 1751 году. В 1754 году Стаббс посетил Италия, чтобы «убедить себя в том, что природа была и всегда больше, чем греческое или римское искусство, и укрепить свою веру, он решил вернуться домой» (Записки Озиаса Хамфри ). В 1756 году он арендовал ферму в деревне Хоркстоу в Линкольншире и провел 18 месяцев в анатомировании лошадей, которому помогала его жена Мэри Спенсер. Он переехал в Лондон около 1759 года и в 1766 году опубликовал «Анатомию лошади» , оригинальные рисунки которой сейчас находятся в коллекции Королевской академии .

Еще до публикации этой работы и благодаря прекрасному знанию морфологии лошади его рисунки считались аристократией того времени наиболее точными среди рисунков его современников, таких как Джеймс Сеймур , Питер Тиллеманс и Джон Вуттон . В 1759 году 3- й герцог Ричмонд попросил его три большие картины, обеспечивающие его карьеру. Благодаря нескольким другим заказам в 1763 году он купил дом в районе Мэрилебон, где прожил остаток своей жизни. Его самая известная картина — это, безусловно, Whistlejacket , картина с гарцующим конем по заказу маркизы Рокингем, которая сейчас находится в Национальной галерее в Лондоне . Эта картина нарушает стандарт однородного фона. В течение 1760-х годов он создал большое количество картин с изображением лошадей, иногда в сопровождении собак или их конюшни. Он также рисовал экзотических животных, таких как львы, тигры, жирафы, обезьяны и носороги, которых он мог наблюдать в частных домах. Он продолжал делать портреты людей. Он выставлял свои картины в «Обществе художников» до 1775 года, затем в новой Королевской академии, более престижной. Стаббс также написал несколько исторических картин.

Early Life and Education

Almost all that is known about the early life of George Stubbs comes from notes made by his fellow artist and friend Ozias Humphry. The informal memoir was never intended for publication, and it is the record of conversations between Stubbs and Humphry when the latter was aged 52 and the former 70.

Stubbs remembered working at his father’s trade, the dressing of leather, in Liverpool, until age 15 or 16. At that point, he told his father that he wished to become a painter. After resisting at first, the elder Stubbs allowed his son to pursue the study of art with painter Hamlet Winstanley. Historians believe that the arrangement with the elder artist lasted little more than a few weeks. After that point, George Stubbs taught himself how to draw and paint.

«Self Portrait» (1780).

Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

What animals did Stubbs paint?

1760–70). Messenger, portrait by George Stubbs. Stubbs also painted a wide variety of other animals, including the lion, tiger, giraffe, monkey, and rhinoceros, which he was able to observe in private menageries.

What was George Stubbs famous for?

horses

George Stubbs ARA (25 August 1724 – 10 July 1806) was an English painter, best known for his paintings of horses. Self-trained, Stubbs learnt his skills independently from other great artists of the eighteenth century such as Reynolds or Gainsborough.

Why did George Stubbs paint?

This meant that he taught students about how human and animal bodies work. Then in 1756 he decided to write a book on the anatomy of a horse. The book was very popular and soon rich men were asking Stubbs to paint pictures of their favourite horses.

How many paintings did George Stubbs paint?

George Stubbs – 82 artworks – painting.

Did Gainsborough paint horses?

This lively and loosely sketched picture of an old horse dates most likely from the mid 1750s, relatively early in Gainsborough’s career when he was still living in his native Suffolk.

How much is a Stubbs painting worth?

A painting by the horse-racing artist George Stubbs has fetched £22.4m at auction. The oil painting, called Gimcrack On Newmarket Heath (1765), has been sold at Christie’s in London by the private Woolavington Collection. The price is a new record for the artist who became famous for his studies of horse anatomy.

What is the meaning of Stubbs?

a person who is an authority on history and who studies it and writes about it.

What are Stubbs paintings worth?

LONDON (Reuters Life!) – A horse painting by George Stubbs fetched 22.4 million pounds ($35.9 million) at Christie’s in London on Tuesday, the third most valuable old master painting to be sold at auction, the company said.

How much are Gainsborough paintings worth?

Thomas Gainsborough’s work has been offered at auction multiple times, with realized prices ranging from $5 USD to $10,515,792 USD, depending on the size and medium of the artwork.

Interest in Horses

From his childhood onward, Stubbs had a fascination with anatomy. At approximately age 20, he moved to York to study the subject with experts. From 1745 to 1753, he worked painting portraits and studied anatomy with surgeon Charles Atkinson. A set of illustrations for a textbook on midwifery published in 1751 is some of the earliest work of George Stubbs that still survives.

In 1754, Stubbs traveled to Italy to bolster his personal conviction that nature was always superior to art, even of the classical Greek or Roman variety. He returned to England in 1756 and rented a farmhouse in Lincolnshire, where he spent the next 18 months dissecting horses and studying the design of their bodies. The physical examinations eventually led to the publication of the portfolio «The Anatomy of the Horse» in 1766.

An anatomical study of a horse by George Stubbs is displayed in a gallery space at Palace House, the National Heritage Centre for Horseracing & Sporting Art on May 2, 2017 in Newmarket, England.

Dan Kitwood / Getty Images

Aristocratic art patrons soon realized that George Stubbs’ drawings were more accurate than the work of earlier noted horse painters like James Seymour and John Wooton. After a commission in 1759 from the 3rd Duke of Richmond for three large paintings, Stubbs had a settled financially lucrative career as a painter. In the following decade, he produced a large number of portraits of individual horses and groups of horses. Stubbs also created many pictures on the topic of a horse attacked by a lion.

Stubbs’ most famous painting is «Whistlejacket,» a portrait of the renowned racehorse rising up on his hind legs. Unlike most other paintings of the time, it has a plain, single-color background. The painting now hangs in the National Gallery in London, England.

Career

Stubbs lived with his mother at Liverpool till he was twenty. He then moved to Wigan and stayed about eight months with Captain Blackbourne, who took a great fancy to him from his likeness to a son whom he had lost. He then moved to Leeds and then to York, where he gave lectures upon anatomy to the students at York County Hospital. His earliest surviving artworks are 18 plates etched for Dr. John Burton’s «Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery» in 1751, which was published only in 1756. From York George Stubbs moved to Hull, and after a short visit to Liverpool set sail for Italy in 1754, in order «to convince himself that nature was and is always superior to art whether Greek or Roman, and having renewed this conviction he immediately resolved upon returning home.» He went by sea to Leghorn, and thence to Rome. He made many sketches from nature and life.While in Italy he befriended an educated Moor, who took him to his father’s house at Ceuta, from the walls of which he witnessed a lion stalk and seize a white Barbary horse about two hundred yards from the ditch. This incident influenced many of his pictures. After his return, Stubbs settled at Liverpool for a while. He came to London in 1756, visiting Lincolnshire on the way to paint portraits for Lady Nelthorpe. In 1758 he rented a farmhouse near Barton, Lincolnshire, where he spent 18 months dissecting horses and preparing for his great work on the «Anatomy of the Horse.» He installed a device by which he could hang the body of a dead horse and move the limbs to any position, as if in motion. He laid bare each layer of muscles one after the other until the skeleton was reached, and produced complete and careful drawings of all. He required a lot of horses before he had finished, and he did the whole work at his own expense and without any assistance. At first, he intended to find engravers to produce drawings for him, but he could not persuade any of them to take up the work, and so decided to execute all the plates by himself. This employed his mornings and nights for six or seven years. «The Anatomy of the Horse» was published in 1766 by J. Purser, and was a great success. It was the first work to define clearly the structural form of the horse. George Stubbs’s reputation as a painter of horses had greatly increased. In 1760 he was at Eaton Hall, painting for Lord Grosvenor. Shortly afterwards Stubbs went to Goodwood, receiving a commission from the Duke of Richmond to paint three large pictures from him. He stayed at Goodwood for nine months, during which time he executed a large hunting-piece, 9 feet by 6 feet, as well as many portraits. In 1760 he became a treasurer of the Society of Artists of Great Britain, later being its president (for one year) in 1773. He was a frequent contributor to the society’s exhibitions from 1762 to 1774. By 1763 he had produced works for several more dukes and other lords and was able to buy a house in Marylebone, a fashionable part of London, where he lived for the rest of his life. Besides his numerous portraits of horses, dogs, and other animals, Stubbs also exhibited two pictures of «Phaeton (1762 and 1764), «Hercules and Achelous» (1770), «Horse and Lion» (1763), «A Lion seizing a Horse» (1764), «A Lion and Stag» (1766), «A Lion devouring a Stag» (1767), «A Lion devouring a Horse» (1770), and several others of lions, lionesses, and tigers.In 1771, at the suggestion of his friend Richard Cosway, the miniature-painter, he started to make experiments in enamel. His first enamels were on copper, one of which was «A Lion devouring a Horse.» Also in the 1770s, he painted single portraits of dogs for the first time, while also receiving commissions to paint hunts with their packs of hounds. In 1775 George Stubbs switched his allegiance to the recently founded but already more prestigious Royal Academy, where he started to exhibit his works. He remained active into his old age. The contributions of his later years included «Reapers» and «Haymakers» (1786), a pair of genre pictures well known from his own engravings.After 1791, in which year he exhibited a portrait of the Prince of Wales, his patron, and three other artworks, he did not contribute to the Royal Academy till 1799. His last project, started in 1795, was «A comparative anatomical exposition of the structure of the human body with that of a tiger and a common fowl», fifteen engravings which appeared between 1804 and 1806. The project was left unfinished. The artist continued to exhibit till 1803, and in 1800 he presented the largest of all his pictures, «Hambletonian beating Diamond at Newmarket».

Is it finished?

The most striking feature of Whistlejacket is the lack of background. This was unusual even in Stubbs’ work and led contemporaries to think it was unfinished. It was not uncommon for a specialist animal painter to work with another artist who would provide a landscape background. Stubbs himself worked with artists including George Barret in exactly this way.

A story grew that the painting was intended as an equestrian portrait of George III, which would have been finished by portrait and landscape specialists and given by Rockingham as a gift to the King. Whistlejacket’s rearing pose certainly mimics royal portraits by artists like Velazquez. It is possible that Rockingham could have intended such a portrait and changed his mind for political reasons.

Сюжеты и мотивы произведений Джорджа Стаббса

Стаббс любил лошадей, он их рисовал и препарировал, изучал и имел доход с любимого дела. Кобылы и жеребята — часто повторяемый сюжет в его работах. Часто он изображал их на фоне деревьев и водной поверхности, что делало силуэт животных более выразительным. Но, как великий анималист, он имел в своем арсенале запас не менее интересных совсем не «лошадиных» сюжетов

Стаббс уделял внимание разным экзотических животным, включая львов, леопардов, зебр, обезьян и носорогов. Их он наблюдал в своих путешествиях, некоторых имел возможность видеть в частных лондонских зверинцах

Он был первооткрывателем кенгуру для британской публики, написав его портрет, имея в распоряжении лишь рассказы очевидцев и шкуру убитого животного.

Особой привлекательностью обладает автопортрет на Белом Охотнике — овальное эмалевое изображение, где автор сидит верхом на охотничьей лошади.

Историческая тематика тоже увлекала Стаббса, но не сыграла важной роли в его творчестве. Реальная востребованность работ Стаббса легко совмещалась с негативным восприятием официальной художественной критики

Художник-анималист и признанный художник — это были несовместимые понятия. «Лошадиное искусство» (а такой термин действительно существует — «Equestrian art») воспринималось три столетия назад как «низкое» искусство, идущее где-то позади портретов, пейзажей, жанровых и исторических тематик. И тем не менее Стаббс стал великим художником в своем направлении

Реальная востребованность работ Стаббса легко совмещалась с негативным восприятием официальной художественной критики. Художник-анималист и признанный художник — это были несовместимые понятия. «Лошадиное искусство» (а такой термин действительно существует — «Equestrian art») воспринималось три столетия назад как «низкое» искусство, идущее где-то позади портретов, пейзажей, жанровых и исторических тематик. И тем не менее Стаббс стал великим художником в своем направлении.

The Anatomy of the Horse by George Stubbs

Submitted by Giles Lane on March 25, 2009 12:17 am

Download A4 | US Letter PDF 1.52Mb

Selected and Introduced for Short Work by Paul Bonaventura, Senior Research Fellow in Fine Art Studies at the Ruskin School of Drawing & Fine Art, University of Oxford

George Stubbs (1724-1806) is recognised as one of the most original artists of the eighteenth century. His singular ability to translate the study of nature into extraordinarily balanced compositions marks him out from all other practitioners in the field of animal painting. Although his wide-ranging subjects also included portraits, conversation pieces and paintings of domestic and exotic animals, Stubbs is best known for painting horses, and his reputation was established among noblemen devoted to racing and breeding horses who recognised in him a shared sympathy for the English countryside and rural ways of life.

Stubbs’s career as a painter of horses was rooted in his extraordinary knowledge of equine make-up. In his early thirties, between 1756 and 1758, Stubbs spent eighteen months dissecting and drawing the bodies of up to a dozen horses at a remote farmhouse at Horkstow in Lincolnshire. Out of this unflinching and painstaking industry came a publication called The Anatomy of the Horse and a steadfast commitment to the pursuit of reality.

In A Memoir of George Stubbs, the only contemporary account of the artist’s life and career, Ozias Humphry described Stubbs’s working methods in Horkstow:

The first edition of The Anatomy of the Horse featured eighteen plates etched by the artist from his drawings, and more than 50,000 words of meticulous scientific text, and its publication in 1766 earned Stubbs instant and lasting appreciation, not least from the animal painters who followed him. ‘ to imagine, for a moment,’ wrote Sir Alfred Munnings, President of the Royal Academy of Arts, ‘Stubbs at his work setting up and dissecting horse-carcasses in the barn there, making detailed drawings, for plate after plate with all the names of the muscles and finally engraving each plate himself, this latter part of the work, an entirely new departure for him, being spread over something like a period of six years, we may then begin to grasp the magnitude of this labour of love.’

Forty-two of Stubbs’s drawings for The Anatomy of the Horse survive in the Royal Academy Collections. Of these, eighteen are scrupulously finished on fine paper, made to be engraved for publication, and drawn to the same scale. The other twenty four are working drawings. Of the eighteen engravings in the accompanying eBook, many have drawings in Piccadilly that directly relate to Stubbs’s original plates. Fifteen of these are from the old set of eighteen, and five belong to the twenty-four working drawings.

The Anatomy of the Horse is a supreme achievement, but Stubbs’s belief in scientific inquiry as the basis for art should not blind us to the fact that his subsequent portraits of thoroughbed racehorses are more than just paintings of record for they absorb us on so many levels; by engaging the personality and feeding the spirit, they compel examination. To see Stubbs’s work solely as a reflection of the Enlightenment aspirations of his aristocratic clients is to neglect its phenomenal aesthetic quality and its lasting, but frequently overlooked impact on the later development of western art.

Paul Bonaventura

Spring 2009

Exhibitions

- 1999: George Stubbs in the Collection of Paul Mellon. A Memorial Exhibition . Yale Center for British Art , New Haven, Connecticut, USA; 2000: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts . Richmond, Virginia, USA

- 2006/07: George Stubbs. A celebration . Exhibition Walker Art Gallery , Liverpool; Tate Britain , London; Frick Collection , New York

- 2012: George Stubbs. 1724-1806. Science into Art. Exhibition in the Neue Pinakothek , Munich.

- 2015: Paintings by George Stubbs from the Yale Center for British Art . Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York

- 2020: George Stubbs: de man, het paard, de obsessie. Mauritshuis , The Hague, February 20 — June 1, 2020.

Legacy

George Stubbs was a minor figure in British art history until the mid-1900s. Famed American art collector Paul Mellon bought his first Stubbs painting, «Pumpkin with a Stable-Lad» in 1936. He became a champion of the artist’s work. In 1955, art historian Basil Taylor received a commission from Pelican Press to write the book «Animal Painting in England — From Barlow to Landseer.» It included an extensive section on Stubbs.

In 1959, Mellon and Taylor met. Their mutual interest in George Stubbs eventually led to Mellon funding the creation of the Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art, which today is the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art at Yale University. The museum connected with the centre now holds the largest collection of Stubbs paintings in the world.

«Whistlejacket» (1762).

Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The auction value of George Stubbs’s paintings has risen considerably in recent years. The record price of 22.4 million British pounds came at a Christie’s auction in 2011 of the 1765 picture «Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath, with a Trainer, a Stable-Lad, and a Jockey.»